William Grimshaw's Narrative

William Grimshaw's Narrative

William Grimshaw's Narrative

William Grimshaw's Narrative

"Being the Story of Life and Events in California

during Flush Times,

Particularly the Years 1848-50, Including a Biographical

Sketch"

Main Webpage on William Robinson Grimshaw

William Robinson Grimshaw was born in 1826 in New York City and enjoyed an adventurous life which is described on a companion webpage. The most complete record of his life is provided in his biography1, "Grimshaw's Narrative" by J.R.K. Kantor. The purpose of this webpage, a supplement to the main webpage on William, is to provide an excerpt from his biography.

Images of Original Manuscript of Grimshaw's Narrative from Bancroft Library

Map Showing William's Travels from San Francisco to the Gold Fields in California

| Title Page |

The title page from "Grimshaw's Narrative is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Title Page from Kantor's Grimshaw's Narrative.

| Images of Original Manuscript of Grimshaw's Narrative from Bancroft Library |

| Preface |

The preface from Kantor's book is as follows:

Of William Robinson Grimshaw’s Narrative, published here for the first time, Bancroft wrote, in his Pioneer Register: "This is not only an interesting sketch of his own life and adventures, but one of the best accounts extant of the events of ‘48-50 in the Sacramento region." Composed in 1872, the Narrative centers on the early Gold Rush period in the Sacramento area, although the earlier section details Grimshaw’s adventures aboard the Izaak Walton and his landings on the coast of California, at Monterey and later at San Pedro. Coming to California thirteen years after Richard Henry Dana, Jr., had shipped on the Pilgrim, Grimshaw’s relation dramatically limns the contrast between the still-arcadian existence of "before the gringo" and the feverish Yankee activity of the mining country. Although the reader of such Gold Rush history has been told often before of the multitude of crewless ships standing in the Bay at San Francisco, nowhere have we found such vivid description of the trip – it took ten days! – from the Golden Gate to the Embarcadero at Sacramento, through the mosquito-infested tules of the delta country. How lucky for Bancroft, and for us more than a century later, that Grimshaw arrived on the Embarcadero to clerk for Sam Brannan just a few months after the news of the gold discovery had spread to the East coast, in late October of 848. But of what he observed, we shall let Grimshaw speak in his own voice.

The Narrative takes us up to April of 1851, when William Robinson Grimshaw married the childless widow of his former partner, William Daylor, and settled down on the Sheldon-Daylor Ranch on the Cosumnes River. The ranch had been granted on January 4, 1844 by Micheltorena to Joaquin Sheldon, i.e., Jared Sheldon. Known as the Rancho Rio de los Cosumnes al Norte, the grant was also referred to as Rancho Omuchumnes, and consisted of five leagues nearby the Sutter grant of New Helvetia…..

What of the later years of Grimshaw? In 1857 he became a law clerk in Sacramento with the firm of Winans and Hyer. In the decade following, through private study and experience in legal matters which his job afforded him, he was found worthy of admittance to the bar in 1868. A few months later, in the spring of 1869, Grimshaw gave up the practice of law, though he retained his position as Justice of the Peace. Poor health led him, in 1876, to journey to the Orient, but the improvement sought by a sea voyage was not forthcoming, and on September 14, 1881, he died at his home. The notice in the Sacramento Union for the 16th of September advised that "friends and acquaintances are respectfully invited to attend the funeral which will take place from his late residence Sunday morning, at 10 o’clock."

"Grimshaw’s place," as the house came to be called, was finally razed in 1949. At present there is a smaller house, constructed from some of the original lumber, on the site of Daylor’s ranch, some eighteen miles from Sacramento where State Highway 16 crosses the Cosumnes River. For the rest, the hills, rising to the Sierra, must look much as they did to Grimshaw more that a century ago.

| Map Showing William's Travels from San Francisco to the Gold Fields in California |

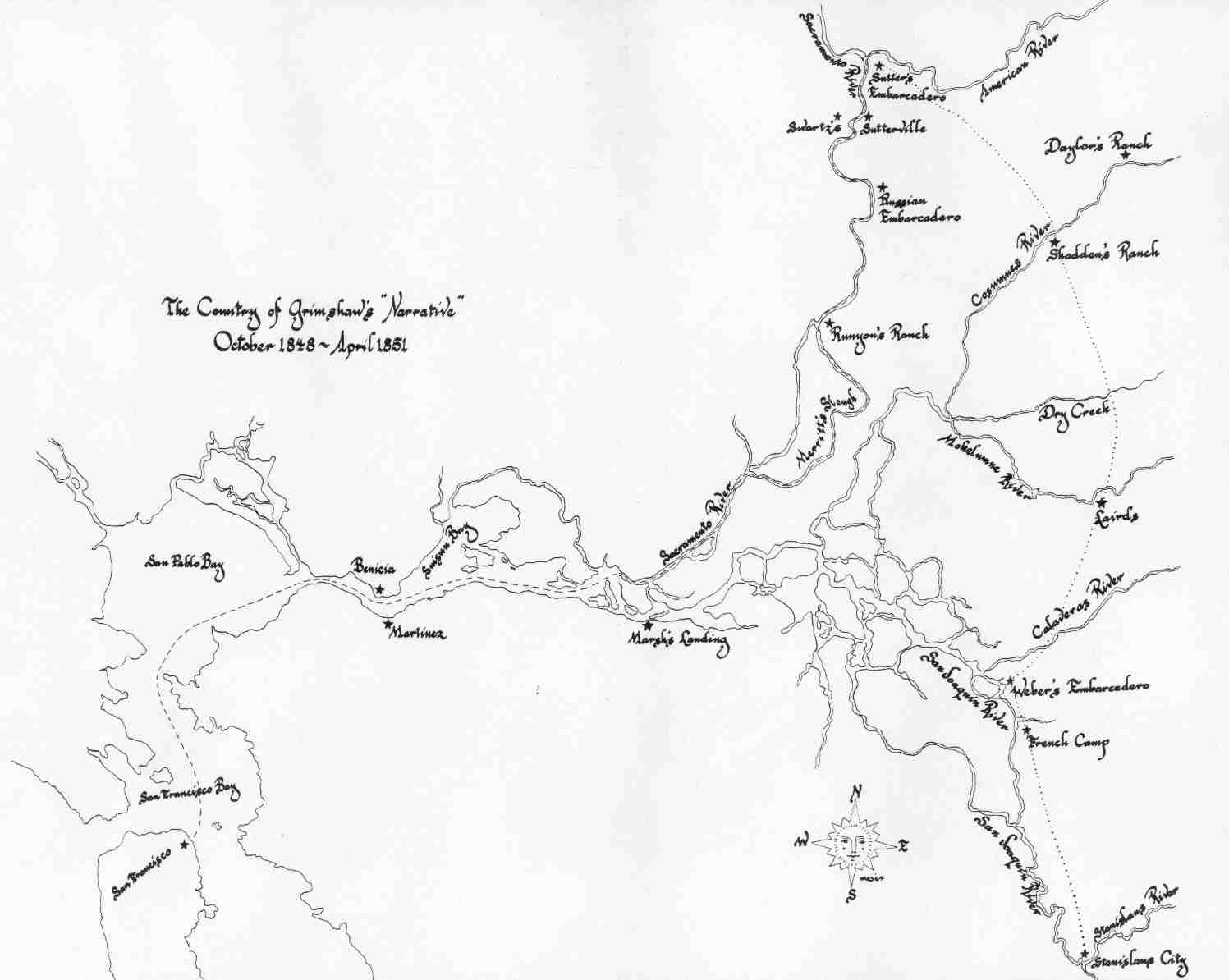

The inside covers of "Grimshaw's Narrative"1 contain a sketch map showing San Francisco, where William arrived in California, and his subsequent travels up the Sacramento River to Sutter's Embarcadero and then south to Weber's Embarcadero. Figure 4 provides a thumbnail for this sketch map.

Figure 4. Sketch map from Kantor's book showing the route followed by William as he traveled from the port in San Francisco up the Sacramento River to the gold field country in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

| Reference |

1

Kantor, J.R.K., 1964, Grimshaw’s Narrative, Being the Story of Life and Events in California during Flush Times, Particularly the Years 1848-50, Including a Biographical Sketch, Written for the Bancroft Library in 1872 by William Robinson Grimshaw: Sacramento, CA, Sacramento Book Collectors Club, 59 p.| Excerpt from Grimshaw’s Narrative1, by William Robinson Grimshaw |

Author's note: This excerpt contains only the text without the extensive footnotes included by Kantor to more completely explain the events related in the book. The reader is referred to the original work for these extensive notes.

Grimshaw's Narrative

Daylor's Ranch.

Sac. Co.

January 20th 1872

MESSRS. H. H. BANCROFT & CO.

Gentlemen:

Your circul[ar] 10th ult. is before me. What possible interest the incidents of a life so uneventful as mine has been can possess for anyone I am at a loss to imagine; but since you ask for them they are hereby placed at your disposal. I must premise by stating that I am not skilled in rhetoric and the facts I set before you must be in the form of a simple narrative, after the manner of Robinson Crusoe.

My name is William Robinson Grimshaw. I was born November 14th, 1826 in a two-story brick house, then a country seat, on the corner of 14th St., & 3rd Avenue in the City of New York. The house is still standing & is immediately opposite the N.Y. Academy of Music.

My father's name was John Grimshaw. He was a younger son of a man belonging to a class called in England "gentlemen farmers," and was born in 1800 near Leids (sic) in the West Riding of Yorkshire. He came to N.Y. at an early age and became clerk for Jeremiah Thompson of that city. Shortly after coming of age he went into business for himself & engaged in cotton speculations so successfully that he soon acquired what was for those days a fortune. He built the house above named and married in the year 1825. Of course having made a fortune so easily he could not discontinue his speculations & (equally of course) before the year 1830 he became bankrupt & had to surrender all his property to his creditors.

My mother's maiden name was Emma Robinson. She is the daughter of Wm. T. Robinson of the mercantile firm of Franklin, Robinson & Co. well known to New Yorkers of the latter part of the last century & was born Sept. 9th, 1803. One of her sisters married Jonas Minturn of N.Y.; another, John B. Toulmin of Mobile (Ala); another became the wife of Wm. Hunter, U.S. Senator from Rhode Island & minister to Brazil in President Jackson's administration. My mother is now living in N.Y. City.

In the year 1830 my father sailed for Liverpool in the ship Mary & Harriet. After remaining in that place a little more than a year he returned to N.Y. in the Ship Sarah Sheaf. I well remember living in the suburbs of Brooklyn, in the cholera season of 1832. About 1833 we again went to Liverpool in the ship Great Britain, Captain French; where my father went into business as a ship broker & where he remained until the latter part of 1837 when we sailed for Mobile (Ala) in the ship Plymouth of Boston, Captain Kenrick.

My father engaged as bookkeeper with John B. Toulmin his brother-in-law for one year. He then became a cotton broker & speculator and died of yellow fever in November 1839 leaving his affairs greatly involved. I lived in Mobile until the summer of 1841 when (my mother not wishing me to grow up in a slave state) my uncle Toulmin obtained for me a situation in the English house of J. L. Phipps & Co. at Rio [de] Janeiro one of the partners of which house (Mr. Eyre) was then in Mobile. I started for N.Y. (there to take passage for Rio,) travelled by land as far as Charleston (S. C.) thence by sea in the ship Sutton, Capt. Avery, and landed in N.Y. in due time. On my arrival my indentures with Messrs. Phipps & Co. were drawn up at the branch house in Pine St. and a passage engaged for me in a brig soon to sail for Rio.

At this juncture a friend of my mothers dissuaded me from going to S. America & induced me to remain in N.Y. He placed me in a wholesale dry goods house, Scudder & Wilcox, who failed in about a year & then my new "friend" left me to shift for myself at the age of 16. I became clerk for various firms in N.Y. & one in Burlington (Vt), near which place my mother was then living, until early in the year 1847 when I gratified a desire which had always been uppermost in my mind which I fear had unfitted me for anything else and shipped "before the mast" as "boy" in Grinnell Minturn & Co's Liverpool Packet Ship Ashburton, Captain Williams Howland (an accomplished seaman, with the manners of a gentleman); lst Mate John McWilliams, a bluff kind hearted Welshman & thorough seaman, now a Captain sailing out of N.Y. I remained in this ship one year and was about to be promoted to 3rd mate. Before becoming an officer, I desired to learn a greater variety of seamanship than could be acquired in short voyages between N.Y. & Liverpool. In February 1848 1 shipped as ordinary seaman on board the Izaak Walton of New Bedford, 800 tons burthen owned by Henry Grinnell and under charter to the government to convey stores & supplies to the U. S. Squadron on the coast of California. The voyage for which we signed articles was from N.Y. to Monterey (Cal) thence, in ballast, to Canton thence with a cargo of tea to N.Y. via the Cape of Good Hope. The Izaak Walton was commanded by Captain Allen; ___Hilts 1st Mate; a young man named Babcock 2nd mate, & a Russian carpenter with a name unpronounceable by any human being besides himself. There were six able seamen; two ordinary seamen, Charles Crandall of Connecticut & myself & I "boy" ___ Lawrence of N.Y. Seamen are rarely known to each other by their surnames which are nearly always "shipping names". i.e. aliases, except Danes & Swedes who are almost invariably Johnsons, Thompsons, Andersons & Harrisons. Other nationalities are simply - Jack, Bill, Tom, Dick & Harry. One of our able seamen called himself Wm. Howland. The shipping name of the inevitable Swede was Tom Newton; his real name be told me was Sjoberg and he was a native of Stockholm. We had a colored steward named Frisbie Hood and a cook also colored.

Howland, Lawrence & Crandall returned to N.Y. in the Izaak Walton. The last I heard from Hood he was at Moquelumne Hill; Newton died not far from where I am now writing in 1852.

Mr. Hilts' tyrannical treatment caused so much dissatisfaction among the crew that at the first port at which we touched (Callao) four of the best men deserted the ship carrying off two boats only one of which was recovered for a reward of $50.00 offered & paid. In place of these men Capt. Allen engaged 4 British "hearts of oak" then in confinement in the Calaboose & who were given their liberty on condition of leaving the place. The life these men caused our mate to lead, by their ' subordination, was some compensation to us for past ill treatment. Soon after leaving Callao, Mr. Hilts for some very slight cause ordered me into the long boat, where I could not defend Thyself, to get a piece of rope for him. As soon as I was in the boat he got upon a water cask and struck me three heavy blows with a piece of tarred "lanyard stuff", a rope thicker than a man's thumb. I immediately went below & refused duty (aided & abetted by the aforesaid "hearts of oak") & vowed to myself to leave the ship at the very first opportunity. I did not return to duty until the vessel was entering Monterey, where we arrived in August 1848. In Monterey were lying at anchor the barque Anita of Boston, and a schooner from Honolulu chartered by a smart Yankee trader who had come to California with an assorted cargo on the first rumor of the gold discovery.

The next morning after our arrival our "hearts of oak" came aft & demanded to be pulled ashore in the boat. As the machinery for the enforcement of the law was very much out of order, owing to the absence of the ships agent Thos. O. Larkin and the unwillingness of Col. Mason to send a soldier outside of the Fort for fear of desertion; and as the captain & mate were rather cowed by the "hearts", their request was, after some bluster, complied with. I have never seen either of them since.

That night, Tom Newton, Hood, the cook & myself borrowed the boat & bid a final farewell to the good ship Izaak Walton. Hood and myself in accordance with a previous understanding with some of the Anita's men, went on board of that barque, where we were hospitably entertained by the crew & stowed away until the barque lift the harbor. I chose this method of concealment because I supposed the last place for our former Captain to look for us would be in a U. S. vessel.

This left the Izaak Walton with the carpenter, 1 able seaman, 1 ordinary do, & 1 boy. Capt. Allen had to wait until November, when Commodore Jones finished him a crew of man of wars men whose terms of service had nearly expired, and the Izaak Walton returned to N.Y.; I have heard by "the Chincha Islands where she took a cargo of guano."

The Anita was chartered by the government as a sort of tender to the squadron. She was commanded by passed Midshipman Selim E. Woodworth, as noble hearted a man and as thorough a seaman as ever trod a deck A seaman can always tell the capacity of the officer placed over him by the manner in which the latter handles his ship. Capt. Woodworth had been detailed from the Ohio, 74, to take command of the Anita. The chief mate was a quarter-master of the Ohio named Williams. The crew were composed mostly of young men from the same ship. There was one elderly man named McDonald (I think) & two others - Abbott and Jim Brady.

Peace having been declared between the U. S. and Mexico, the Anita was under sailing orders for Santa Barbara, San Pedro & San Diego having on b passengers Major Rich, pay master, his son acting as 1 his clerk; Captain Matt, son of Colonel Jonathan D. Stevenson; an army surgeon whose name I do not remember & Major Rich's colored servant.

The Anita could not safely proceed to sea with only three men. That number was not sufficient to handle the vessel; besides it was impossible for three men to steer the barque unless the chief mate "Stood a trick" at the wheel during his watch on deck which would not be compatible with his dignity. Somehow Capt. Woodworth must have found out that a seaman was lying perdu in his ship. At any rate he took fresh provisions on board; obtained two fort to assist, as amateurs, in working the a. As soon as the "Amateurs" found themselves in blue water the[y] went off duty from sea-sickness and were absolutely useless for the rest of the voyage except when the barque was at anchor.

Arrived at Santa Barbara and there found the barque Joven Guipuzcoana (Young Maid of Guipuzcoa), now a dismantled hulk in Sacramento, manned by a crew of native Californians.

I forgot to mention that as soon as the Anita had rounded Point a Pinos, Hood and I emerged from our place of concealment & went aft into the cabin where we signed shipping articles; Hood as steward, I as able seaman.

At Santa Barbara we received on board a few men from the now disbanded Company F, Stevenson's regiment, who offered to assist in working & loading the barque for their passage to San Francisco.

In a few days set sail for San Pedro. Here the bluff above the landing & close to the Custom House (adobe) was strewn with a considerable quantity and an endless variety of implements, munitions & spoils of war. Among the last mentioned were a number of brass cannon, 12 or 14 feet long and a century or two old as shown by figures cast in them; taken from the Mexicans at Los Angeles. To get these on board we had to tow the Anita's long boat & moor her just outside the surf, there being no wharf. A gun was then rolled down the cliff. As many men as could stand alongside then placed handspikes under and at right angles to the gun; a man at each end of the handspike. The gun was then lifted, carried through the surf, breast deep, and placed very carefully (lest it go through the bottom) into the boat. At a distance, a party of men thus engaged looked like a magnified centipede. The guns were brought off one at a time; and the rest of the paraphernalia of war were embarked in the same manner. This, while it lasted, was quite as arduous as the boating of hides described in 2 Years before the mast. We here obtained some more men from Stevenson's regiment.

During our stay in San Pedro, we had to procure a supply of fresh water this being the only place on the coast except Saucelito where it could be obtained. At the head of the creek where Wilmington is now located, is, or was, a spring of fresh water covered with salt water at high tide. We had to place a water cask in the long boat; tow the latter to the head of the- creek, - which could only be done when the tide served (sometimes at midnight), wait until the tide ebbed, fill the cask, wait until the tide floated' the boat and pull back to the ship. We would sometimes leave the barque at noon or a little after and not get back until late the next forenoon. This had to be repeated until every cask in the ship was filled. Take it altogether the port of San Pedro is not endeared to the sailors of those days by recollections of a pleasant nature.

One Sunday the crew had a day's liberty ashore. We walked about six miles on the road to Los Angeles, and stopped at a large grazing farm called the "Rancho de los Palos Verdes" probably because there was not a tree nor a solitary green place except cactus of which there was great abundance. The lady of the house (I think one of the Martinez family) had a pure Caucasian complexion & cast of features. We asked her for dinner which was soon got ready by the Indian servants & consisted of the inevitable & invariable tortillas (very similar to Scotch bannocks or oat-cakes), frijoles (beans), and chili colorado (jerked beef stewed with red peppers), a full meal of which I judge would remove the skin from the inside of the mouth and produce inflammation in the stomach of a man not seasoned to the dish by degrees. No tea, no coffee and although hundreds of cattle were in immediate view & thousands on the rancho, no milk. The only drink to be obtained was that most wretched tipple aguacaliente. Of course, the party being composed of soldiers & sailors, most of them had to get drunk, quarrel with some of the men about the ranch (fortunately limited to words), and return to the ship in a dilapidated condition.

Having taken our cargoe on board, filled the water casks & obtained a supply of fresh beef for our now large ship's company, we hoisted anchor & set sail for San Diego. Captain W. D. Phelps of the hide drogher Tasso, of Boston, was on board and "worked his passage" by piloting us down the coast and into the harbor of San Diego. I wonder if the old gentleman remembers that pleasant September morning when he was so much embarrassed in directing the man at the wheel, by the Anita's tiller working abaft the rudder head. Arrived at San Diego the next day after leaving San Pedro.

We remained in San Diego a week or ten days and left the harbor bound for San Francisco. After passing Point Conception we encountered a severe N. W. gale with so high a sea running that nothing could be cooked in the ships galley and for 3 days we in the forecastle had to live upon hard bread & raw salt pork. In this gale we reefed topsails for the first time since leaving Monterey nearly three months before. Think of that ye mariners of the North Atlantic.

Arrived in Monterey we found a portion of the U. S. Squadron at anchor. There were the Ohio, 74, Commodore Jones' flag ship; the frigate Warren, the sloop of war Dale; the store-ship Southampton, & I think the Cyane. Here also was the Izaak Walton. Every possible precaution was taken to prevent the desertion of men from the squadron. At sunset the boats of the various ships were hoisted in on deck or up to the davits, and after that no boat was permitted to leave a ship on any pretext whatever. In spite of all this as man men as the Ohio's launch could carry managed to desert from that ship. The boat had been detained at the landing until after dark. When she reached the ship, officers & boats crew went up on deck leaving two boat keepers ("boys") to bring the launch around to the tackles. Scarcely was the boat headed for these latter than as many men as she could well ca rushed through the lower ports, jumped into the boat, seized the oars, pulled to the nearest part of the shore beached the boat and made their escape. As they passed the vessels that were near their course, they answered the usual hail (it being after dark) by answering "Ohio's launch" and, of course, were suffered to proceed. Before the officers bad time to recover from the surprise caused by this daring act the men were far out of sight & hearing. The two boat keepers brought the launch back to the ship and for their fidelity were given their discharge from the navy the next day. Two of the Warren's men were caught attempting to desert and the barbarous punishment of flogging through the fleet was inflicted upon them. I have seen frightful whippings inflicted on wrong-doers by the people (sometimes called "mobs") and have heard much sympathy expressed for them; but never have I witnessed anything to compare with the wretched condition of these two men whom I saw on board of the Warren that night.

In a few days [we] sailed for San Francisco where we arrived in the latter part of October. Here were the ships Huntress of N.Y., Capt. Spring; Rhone of Baltimore; & Laura Ann of Liverpool; the teak built barque Janet of Calcutta, Captain Dring, abandoned by all hands from the captain to the cook. In addition to these were some up-river craft; among them Capt. Sutter's launch Sacramento, manned by Indians, and a sort of scow, schooner-rigged, called the Londresa, which I supposed to [be] Spanish for laundress.

The mines were now in full blast. The mad rush for gold had set in and the auri sacra fames had taken complete possession of men's minds. Every soul who could get away, with the exception Of a few "beach combers", "long shore men", and vagabonds always hanging around a seaport, had left. I remember that the frame of the Parker House had been raised but the work had been abandoned and did not seem likely to be resumed. A wharf at Clark's Point partially constructed was left unfinished. The boat landing, at high tide, was at a sort of mole at the N. E. comer of Clay & Montgomery Streets in the rear of Sherman & Ruckle's Store. At low tide the landing was at a pile of rocks about the comer of Broadway & Sansome Sts.

I have never seen any account of the fearful amount of sickness that afflicted the first white comers to the mines, nor of the great mortality which took place among them in the autumn & winter of 1848. Many a poor fellow sick & emaciated found his way from the mines to San Francisco to fill a nameless & unrecorded grave and to be instantly forgotten in the prevailing excitement. Never was the maxim "every one for himself" so literally carried out. I think that the mortality that season taking into account the number of the population was greater than it has ever been since; even in times of cholera & small-pox.

While we lay at anchor - the mate & I being the only ones on board - a small schooner having an ensign with the design of a pick & shovel at her peak, rounded too close to us and dropped anchor. A boat's crew, all apparently intoxicated, put off from her & pulled ashore. Soon after a man appeared on deck & hailed the Anita. We could make nothing of what he said, and Mr. Williams ordered me to scull the jolley boat off and see what he wanted. On boarding the schooner I found the man maudlin drunk, crying & saying there was a dead man somewhere on board - where, he did not seem to know exactly. I went into the little cabin but could find no one. I thought the man was under some delusion, but finally descended the hatchway into the hold and crept along aft on the ballast, it being quite dark. Presently I came across a man lying on some blankets & said "halloo, shipmate." No answer. I then felt of him and found that he had been dead some hours. Part of the men came back to the schooner, took the body ashore & buried it. No one knew his name, nor where he came from. He had engaged his passage at Sutter's Embarcadero, his name not being asked, had taken blankets, lain down on the ballast in the hold & died. This was the case of one out of hundreds who lie in unknown graves in the mines & in other parts of Upper California.

In the year 1847 Mrs. Thomas Rhoads, living on the Cosumnes River, 20 miles from Sutter's Fort, was taken sick from disease of the liver. There was no physician worthy of the name & very little medicine outside of San Francisco. After lingering some months Mrs. Rhoads, growing rapidly worse, her husband thought it best that she should be removed to San Francisco for change of climate and to obtain proper medical attendance. A bed was made in a[n] ox-wagon (Mrs. R. being unable to sit up) and on this she made the trip to the Embarcadero by night, the heat being too great for a sick person to travel in the day time. At the Embarcadero Capt. Sutter s launch, loaded with wheat in bulk to the combings of the hatchway, was about to sail for San Francisco. On this wheat Mrs. Rhoads' bed was made and the launch started down the river. When they got as far as Benicia, and the patient inhaled the sea air, she died & was buried at that place. Her husband paid a man to place a headboard at her grave, and to build an enclosure around the place where she was buried. The man failed to execute the trust and to this day the children of Mrs. Rhoads have been unable to find the spot where lie the remains of their mother.

One day there came to anchor the whale-ship Flora of New Bedford, she having touched at San Francisco for water & fresh provisions. The captain went ashore in a boat manned by two youngsters & proceeded to the office of the ships agent. There he was told of the state of affairs & advised to go back on board of his vessel & to leave the place at once or he would lose every man of his crew. Accordingly the captain hastened to return to his ship. While the boat was awaiting his return from the agent's, one or two loungers got into conversation with the young men in charge of her and gave the latter their views of the situation. These views were soon communicated to the crew of the Flora. In a short time the anchor was hoisted, the to sails sheeted home and the ship's head pointed for the Golden Gate. Then commenced a grand disturbance with the usual loud talk, threats, & gesticulations. Next, the ship was put about & again came to anchor. The ensuing day most of the crew left, with the understanding as we were told, that they should proceed to the mine[s], that one third of the gross proceeds of their labor should be paid to the owners of the Flora, and that the men should not forfeit their "-lay-". No doubt these owners or their descendants are now revelling in the wealth acquired by that crew in the mines of California. In a few days the Flora obtained a miserable apology for a crew giving them $100.00 each for the "run" home and again put to sea; the whaling voyage of course coming to an abrupt end.

Posted around San Francisco was a placard stating that a reward of $5000.00 would be paid for the apprehension of Peter Raymond, who murdered John R. Von Pfister at Sutter's Mill, or for his head in case he could not be taken alive.

Edward H. Von Pfister, the murdered man's brother, is now living in Benicia.

On the arrival of the Anita at San Francisco the crew were paid off & Capt. Woodworth obtained his awaited furlough. The barque's next voyage (the charter to government having nearly expired) was to be to Oregon for a cargo of provisions. Mr. Williams was to take command; and he offered me the berth of 2nd mate which I accepted, not wishing to give up a sea life and being, I suppose, too young to become infected with the prevailing madness for gold. I accordingly remained in the barque as a sort of deputy ship keeper (the Anita still drawing, rations from the quartermaster) In the meantime Capt. Woodworth, the natural goodness of whose heart prompted him to take an interest in the welfare of an almost entire stranger - questioned me as to my ability to do other duty beside that of a seaman, earnestly advised me to give up a sea life and induced me to agree to accept a situation as. clerk, which he promised to procure for me ashore. The first situation offered was that of bookkeeper at Weber's - pronounced Weaver's - Embarcadero (now Stockton), wages $16 per day. The present incumbent had come to San Francisco sick & not expected to live and his predecessor had died at his post. This offer I declined. In about a week I met Mr. Brannan at Mellus & Howard counting room and entered into an engagement with him as bookkeeper for one year at his store at Sutter's Fort. A few days afterward I took my hammock & sea chest (which I had saved on leaving the Izaak Walton) on board of the launch Susanita, a ship's longboat decked over schooner rigged. This launch had been purchased from John J. Vioget at a cost of $10,000.00 She rated a "white Captain" & 4 Kanakas. Just upon the point of sailing the captain demanded to be paid off and went upon a frolic. Mr. Brannan placed me in charge of the launch, giving me as mate and, what was of paramount importance, pilot, a very intelligent Kanaka, one of the crew. We had four new comers from Oregon as passengers. These latter were kindhearted, simple-minded men, but I thought them the roughest set of human beings I had ever encountered in my life; even in a ship's forecastle. Since then I have met a great many rougher & more uncouth even than they.

On our voyage to Sutter's Embarcadero we passed one house at Benicia - Capt. Cooper's, - one at Martinez, one near the mouth of the Sacramento, built by L. W. Hastings, somewhat pretentiously styled "Montezuma", and Swarts tule house two miles below the Embarcadero. There was a house occupied by Tobias Kadell 8 miles by land below Sutter's Fort on the E. bank of the river at a place called the "Russian Embarcadero"; so named because here in former years the Russian launches came to receive cargoes of bides, tallow & wheat, in which commodities Capt. Sutter paid for a large tract of land at or near Bodega purchased from a Russian company. The place is now the town site of Freeport. In passing through the narrow Steamboat Slough (then called Merritt's) the branches of the large Sycamore trees growing at the rivers edge met and formed an almost continuous arch overhead. From the Slough up, the trunks and branches of the trees protruded from the ba out over the river on each side. it will be readily imagined how difficult was the navigation for small craft drifting with the rapid current at the time of the Spring freshets having no steerage way. Before the grand rush in 1849 these obstructions were mostly removed and the intricate channel through Suisun Bay, buoyed out.

At the head of the slough we tied up to the east bank of the river where was a large rancheria of Indians. This place is now a part of Runyon's Ranch. One of our Oregon passengers took his rifle, went about 100 yards from the river's edge and returned in a short time with a deer which he had shot. At night the tule west of the Sacramento would sometimes be burning and the elk & deer running affrighted before the fire would make a rumbling like distant thunder.

In about ten days - an average passage - we arrived at Sutter's Embarcadero and made fast to some Sycamore trees, at the outlet of Sutter Slough and just above what is now the foot of I Street. Here was a spit of sand something like a small strip of sea beach.

The only vessel here was the barque Providence, dismantled and fitted up as a store by George McDougal and William (afterwards Judge) Blackburn. This vessel was moored to the river side and on the bank above was a board shanty in which lived the firm above named, Wm. Nuttall, their clerk, and my old shipmate, Tom Newton, porter. Mrs. D. was living under the protection of McDougal as his mistress.

This shanty was at that time (November 1848) the only building where now stands the City of Sacramento. There was a rancheria of miserable Indians, who appeared to live by fishing, and a lot more were encamped across the outlet of the Slough. A the rest of the place was a complete wilderness. For one third of a mile back from the river were great numbers of oaks & sycamores, some of them of very large size. Under these trees was a heavy growth of grass and, in the low places, a dense jungle of willows & vines which extended down to the water's edge. A narrow road had been cut, extending from the landing to what is now the comer of J & 2nd Streets; thence to K and 5th; thence about L & 8th and along L past the South side of the Fort. This road was utterly impassable during a wet winter. The way in which Sacramento was built in this swamp instead of upon the more eligible location of Sutterville (surveyed years before) is a part of history. I will venture the assertion that never before were business men so completely taken in and done for by unscrupulous land speculators.

The firm of S. Brannan & Co. was composed of Henry Mellus, W. D. M. Howard, Talbot H. Green, Samuel Brannan and William Stout. Their store was an adobe building of one story about 100 feet long by 30 wide situated about 50 yards East of the fort. There was a loft filled with hides and other relics of trade before the mines were discovered. The building had been erected by Capt. Sutter for the use of emigrants who were without shelter, and somehow acquired the name of the "old penitentiary." After Brannan & Co. vacated this building it was occupied as a hospital by Alex. G. Abell & Charles Cragin of Washington, D. C. It was then used as a brewery by M. Yager and the last vestige of it disappeared in the flood of 1862.

The only other building outside the Fort was a small adobe house not far from the South gate. It bore the legend "Retail Store S. Norris and had formerly been used as a shelter for Sutter's vaqueros.

When I entered upon my duties as bookkeeper, Jeremiah Sherwood, late captain in Stevenson's regiment, was head clerk & manager. Another salesman was Tallman H. Rolfe, now of Nevada City. James Rowan was teamster afterwards succeeded by an old pioneer named Atkinson, generally known as "Old Wheat." There was a branch store at Mormon Island, in charge of James Queen, late of Stevenson's regiment, which was discontinued in the Spring of 1849, and Queen became salesman after the store was removed to the Embarcadero. A branch store at Sutter's Mill had been discontinued a few weeks before I came, and the books were handed to me to write up. Some of the names in the ledger were quite original. Running accounts had been opened with "Pete", "Taff", "Welsh Sam", "Dancing Jim" and others of the same sort. I made out the bills in these names, but the collection of them was no part of my business. My predecessor as bookkeeper was Edward L. Stetson (since deceased) who had to give up his place on account of protracted sickness.

If the books which I then kept were now in existence I think they would possess great value. In them were entered the names of all of the original settlers in the Sacramento Valley; and the large amount of business transacted as well as the enormous profits obtained, as shown by them, would excite great curiosity at the present day. I have in my possession a page from an old blotter, one charge on which is 20 lbs. Saleratus $400.00; Glass beads for the Indian traders $20.00 per lb (original cost about 5 cents per lb); Boston Crackers $16.00 per tin; Common hard bread 75c per lb.; Sardines $5.00 per box; champagne $10.00 per bottle ($15 to $20 in the mines); and abundantly consumed Ale & Porter $5.00 per bottle; Seidlitz powders $5 per box. Quinine sold for its weight in gold $16 to $20 per ounce & the supply never met the demand.

John S. Fowler gave an oyster supper to some of his friends. We had in the store I dozen 2 lb. tins Baltimore Oysters for the lot $144.00 was asked and paid without a murmur.

One of Brannan & Co's team mules had his shoulder galled by the collar & some spirits of turpentine was required. Having none in the store, we sent to a small drug establishment in the fort and procured two thirds of a tea cup full, price $5.00. At this charge Mr. Brannan murmured audibly.

The blacksmith & gunsmith of the fort (I may as well here state that the place was not known as Sutter's Fort but as "New Helvetia" in which name letters were dated & account books and bills headed) was Ephraim Fairchild. For the smallest job on gun or pistol the charge was $16. For shoeing [a] horse or mule 1 shoe $16.00. Shod all around, 4 ounces ($64.00). He had an assistant to blow the bellows & strike on the anvil - whom he paid $16.00 per day.

During the winter a man named Joseph Wadleigh (if I remember rightly) made his appearance with a set of tinners tools and a supply of tin plate. He put up a cabin between Brannan & Co's store and the fort and engaged in the manufacture of pans of the size and pattern of milk pans. These were as indispensable to the miner as pick or shovel & sold readily at $16.00 each, with a small discount by wholesale to merchants & traders. Sitting at my desk, Wadleigh's song with tap, tap, tap accompaniment went on all day long. No matter how late one retired to bed, nor how early one rose in the morning, the inevitable tap, tap, tap was going on and all hours. Before summer Wadleigh who accumulated a fortune which he was wise enough to take to his home in the East & which I hope he still lives to enjoy; for a more light-hearted, jovial fellow I never met.

In those days when a man purchased anything he never asked the price until he took out his purse to pay for it. A trader from the mines would leave a memorandum of the goods he wanted and betake himself to some place of amusement. When the goods were delivered he merely glanced at the sum total of the bill and handed out his sack of gold. Credit for an outfit to the mines was readily given to runaway sailors, deserting soldiers and other entire strangers; if the debtor lived to return, the debt was sure to be paid. As goods were hauled from the Embarcadero, they were unloaded outside the store and put away at leisure. If they accumulated so that there was a quantity outside at bedtime the doors were locked and the goods left all night. Although there were packages of all sizes from a barrel of beef or pork to a packet of needles not an article was ever missed.

Early in the Spring of 1849 we balanced the books and made a remittance to S. Francisco of $50,000.00. The gold was put in buckskin sacks; these were nailed up in a strong wooden box which was sent on board of the launch Dice mi Nana and delivered to the Captain (I think Charles H. Ross). I doubt if we went through the formality of taking a receipt.

Our lst Alcalde, we being nominally under the Mexican law, was Frank Bates (brother of state treasurer Bates). Our 2nd Alcalde, John S. Fowler. These offices were non-stipendiary and as far as any criminal business was concerned absolute sinecures. The first call on the alcaldes to exercise their criminal jurisdiction arose from the killing of [Isaac] Alderman, an Oregon desperado, by Charles E. Pickett, when the two promptly resigned their offices.

Here the matter would have ended, the homicide having been committed purely in self defense, but for the action taken by Mr. Brannan who called a meeting of the citizens, earnestly advocated action by the people and succeeded in organizing a court before which Pickett stood his trial, & was acquitted, Mr. Brannan acting both as judge and as prosecuting attorney. You will find a rough sketch of this trial (written by me) in the Sac. "Daily Union" in the spring of 1854. I recommend you to look it up; the names of many persons engaged in it having escaped my memory.

Not the slightest attention was paid to Sunday. Buying, selling, trading, hauling goods, drinking, gambling and sometimes fighting went on exactly the same one day as another.

Although we had no government, no courts, no judges, no sheriffs, no churches, no preachers, no taxes, never before or since existed a community where every man's rights were so sacredly respected by his fellow men.

In the winter of 1848-49 the roads to the mines were m so bad a condition as to be nearly impassable for loaded wagons, and freights enormously high. John S. Fowler owned several ox teams which were driven month each. Gold was being taken out in large quantities, & goods of all descriptions rapidly consumed. The supply of these goods had to be kept up at any cost. All that Winter, Fowler asked & obtained $2000.00 per ton freight to Sutter's mill or Dry Diggins, 50 miles distant from New Helvetia. No complaints of monopoly or "grasping corporations".

In early days great numbers of coyotes (prairie wolves) roamed over the Sacramento Valley. On a cold night they would come right up to the store and prevent all sleep by their short quick bark, until someone got up & drove them away.

One day Charles Mackay of Oregon, mounted on a Cayuse (pronounced Kiuse) pony, was talking with Mr. Brannan in front of the store. One of these coyotes was seen sneaking off in the distance. Mackay gave chase to the coyote, lassoed him, took a buckskin thong from his saddle and muzzled him, took another and tied his forelegs, then came back on a full gallop and threw him down on the ground. This was done without getting out of the saddle and, most of the time, under full gallop.

In the centre of the inside of the fort was a two story adobe building, still standing, the lower portion of which was used as a bar room with a monf6 table or two in it. This bar was crowded with customers night & day and never closed from one month's end to the other. The upper story was rented by Rufus Hitchcock & wife for a boarding house. Board was $40 per week; meals $2 each. The fare was plain and simple. We had plenty of fresh beef, beans, bread (mostly in the form of "biscuit"), tea & coffee, no milk. Sometimes butter made its appearance; sometimes not. The few potatoes & onions that came into market were sent to the mines as a cure & preventive of scurvy and brought such enormous prices ($1.00 each) as placed them entirely out of reach as an article of food.

Early in the Spring Mr. Brannan came to our rescue in a dietetic sense. He erected a shanty alongside the store and, for our benefit, hired a cook (Ch's Lewis, colored, afterward succeeded by Louis Keeseburg & wife).

The Hitchcock family consisted of Rufus Hitchcock, his wife one son & two daughters. They are all long since deceased except one daughter, Mrs. Tappens, who now lives in Oregon.

About the month of January, 1849, a man arrived at the fort from the Dry Diggings, as the ground now covered by Placerville & environs was called, who could not stand upright on account of the condition of his back, caused by a severe whipping inflicted by the miners. Much sympathy was excited in behalf of this man. As I have never seen any account of this affair in book or newspaper I hereby give a few of the particulars, with the causes which led to what the reporters call a "tragedy".

When Pete Raymond murdered Von Pfister the previous summer he was arrested and taken to Sutter's Fort where he was handed over to the officers of the law. He was confined in a cell from which escape was deemed impossible & M. J. House appointed as his guard for the night. In the morning Pete was discovered to have made his escape - many thought by the connivance of his guard. In a few days an Indian gave information that Raymond was at Swartz's - a tule house on the West bank of the Sacramento opposite Sutterville. Mr. Brannan at once organized a party who went after the escaped prisoner. The party rode on horseback to Sutterville where they obtained a canoe and started for the opposite bank of the river. When nearly across, the boat was capsized and the noise made by a lot of men in the water gave warning to Raymond who betook himself to the tule and was never after heard of.

The miners then resolved that the next crime committed in their midst should be punished by themselves.

Some time afterwards a party of three men, one of them our friend of the lacerated back, were playing poker in a bar room tent at the Dry Diggings at a late hour of the night. One of them lost all his money. The three then present the proprietor, compelled him to give up him with death in case he disclosed the rob next day the affair leaked out; the 3 men were arrested, tried & convicted & a merciless whipping inflicted upon them. They then made threats to the effect that those who took part in the proceedings were marked men; that they would not live to whip anyone else, etc. The miners then took two of the criminals and hung them, the third having been got out of the way by his friends and sent down to the fort by night This gave the Diggings the name of Hangtown by which it was known for many years afterward.

What few crimes were committed in the then limited area of the mines met with equally prompt punishment and this may have had a tendency to keep the "lower strata" in the paths of rectitude as I have before stated.

About April or May, 1849, E. C. Kemble & [George] Hubbard brought to New Helvetia a hand-press and type to start a newspaper, - the Placer Times. Of course the event had to be celebrated by a festival. I went 8 miles down the river to the house of Tobias Kadell, now Freeport, and purchased 2 or 3 dozen of eggs. The family of M. T. McLellan, who then kept the boarding house in the fort, contributed a sufficient quantity of milk. Some choice spirits assembled in Brannan & Co's counting room. Two pails of egg-nog (the first ever made in the place) were drunk. Champagne ad libitum was then brought in and the festivities kept up until a late hour. Many of the party awoke the next morning with severe headaches. Mr. Hubbard returned to San Francisco. Mr. Kemble was soon taken sick & went off duty as editor. Mr. Brannan then wrote the editorials, Tallman H. Rolfe set the type & at the end of the week struck off an edition of the paper. A cloth shanty had been erected a short distance North of Brannan & Co's store and this continued to be the office of the Placer Times until all business was removed to the Embarcadero.

In the month of December the new town was surveyed and plotted b Lieut. Wm. H. Warner, U. S. Army, and named "Sacramento." Mr. Brannan paid a newcomer named Barlow $100.00 to delay his journey to the mines & make Brannan a map of the town. On this map Brannan & Co, Hensley, Reading & Co, Priest Lee & Co., P.H. Burnette & S. Norris divided - not without some contention among themselves - the lots which Capt. Sutter had agreed to convey to- them and then commenced the fierce rivalry between Sutterville, surveyed and plotted in 1844,1 and the new town, which should be the centre of trade. This contest lasted all Winter & Spring; every inducement was held out to new-comers to locate in one or the other of the two towns. Geo. McDougal & Co., L. W. Hastings, Henry Cheever, Josiah Gordon and George McKinstry... were the champions of Sutterville. The Gentlemen I have named in connection with the new town were the advocates of Sacramento. The Sutterville men pointed the natural superiority of their location on high ground; averring that the site of Sacramento was a mere swamp and subject to overflow. This latter statement was flatly denied by those interested in Sacramento; who insisted that the highest point on a navigable stream where loaded vessels could meet teams from the interior was the place for a town. The winter of 1848-49 was not a wet one; the Sacramento river did not rise above its banks and this fact gave plausibility to the assertions of the Sacramento men. The struggle lasted until the grand rush of the world to California when Sacramento finally triumphed. How terribly the men who invested in Sacramento were undeceived on the night of January 8th 1850 is a part of the history of the country.

During all this contest, Capt. Sutter had quarrelled with his son, John A. Jr. Both had quarrelled with their agent, Peter H. Bumett, and had revoked his powers. It would be unpossible to imagine two men more thoroughly unfit for business of any kind than the elder & younger Sutters; so the old gentleman, overwhehned by the fierceness of the struggle going on around him, stood aloof and signed any and all papers presented by his "friends".

On the 1st of May 1849 the partnership of S. Brannan & Co. was to expire by limitation. About the middle of April Mr. Stout was engaged with a surveying party, at the head of which was a Mr. Hall, a large, portly, jolly Englishman, in laying out a town (of great promise) at a point on the Stanislaus river about 8 miles above its junction with the San Joaquin and distant about 80 miles from the fort.' It was necessary f or Mr. Stout to be present at the settlement of the partnership. There was no method of communicating with him except by special mess[enger] and that message I volunteered to convey. With some reluctance, - for the streams I had to pass were all "bank full" - Mr. Brannan consented to let me go. I was furnished with two saddle horses, that being the only means of travelling, and a pair of blankets, without which a man would no more have thought of making a journey than without his boots or hat and started riding one horse & leading the other. My road as far as French Camp... (beyond Stockton) was the old train from Monterey to Sutter's Fort - now called the upper Stockton road. The first thing to excite the wonder of the traveller was the vast number of wild fowl. It is impossible to give an idea of the quantity of these. One flock of ducks would cover acres of appear to be numbered by millions. As the horses passed along the road the geese would move out of the way from 10 to 20 feet on each side and it seemed to be impossible to realize that they were not tame. Herds of antelope were always in sight; so were numbers of the prowling coyote.

I passed the adobe cabin of Martin Murphy, on the upland North of the Cosumnes river, just before sunset. My horse floundered and struggled about 1/2 mile through a piece of miry bottom land, nearly throwing me off which brought me to the bank of the river opposite the house of Thomas J. Shaddin where I was to stop for the night. The method of crossing the stream was very primitive. The river was about 60 feet wide but "bank full' and very rapid. A quantity of tule had been bound together so as to form a solid boat or raft. In the centre of this the passenger placed his saddle bridle and blankets and knelt down immediately abaft of them. A piece of rawhide was stretched across the ferry and by this the ferryman standing on the forward part of the "boat" pulled her across. The horses were then made to swim over. It, as not without misgiving that I trusted myself to this frail structure but there was no choice; and in crossing other streams on my journey I would have been thankful for even this means of ferryage.

I found "Shaddin's Ranch" to be a cabin composed, both sides & roof, of the never failing tule, with some bunks placed against the walls inside. A hole was left about the centre of the roof under which on the ground there being no floor a fire was built, round which the family & other inmates gathered. Since the opening of the mines an adobe building with fireplace & chimney had been added. At "bedtime" I laid the mochillos (pronounced macheers & so spelled by Joaquin Miller) of my Mexican saddle on the ground under the eaves of the "house", outside. On these I placed my blankets and the saddle made an excellent pillow.

The next morning I was called at an early hour. My horses were driven up in the caballada belonging to the ranch (no stubble, hay or grain) and after breakfasting & paying my bill I again started . At intervals on the road my horse would struggle and flounder in the mud so that it was with great difficulty I retained seat in the saddle. Ten miles from Shaddin's the road was intersected by Dry Creek which was "bank full". About 100 yards above the road the creek was spanned by a fallen tree. Across this I crept carrying my saddle & blankets in two trips & drove in the horses to swim. I caught them after some trouble and resumed my journey. At noon came to the Moquelumne opposite the house of Laird, lately owned by McKinzie."' Here was a canoe for a ferry boat.

About the middle of the afternoon had to cross the Calaveras. Here was no tule boat, no canoe, no log. According to previous instructions I loosed the cinch or girth of my saddle, placed my watch in my hat and plunged into the stream riding one horse and leading the other; taking great care not to let my horse be carried below the "coming out place." The water came half way between waist & shoulder. Emerging from the creek I had to ride in my wet clothes on a chilly afternoon six miles to Stockton.

In crossing these streams & others with loaded teams, it was customary to unload the wagon; to take the goods across a few at a time; then draw the wagon across with ropes & swim the horses. Before starting on the journey a barrel of pork was emptied and the pork placed in sacks for convenience in unloading.

I have been somewhat minute in describing this method of crossing streams on a journey because I have never seen any mention made of it before, and because I think that although in those days we were not oppressed by "soulless corporations" or "grasping monopolies" the comfort of the travelling public was not so well looked after as at the present time.

Rode into Stockton (then known all through the country as Weber's - pronounced Weaver's - Embarcadero) where I was indebted to the courtesy of James Wadsworth for the privilege of laying down my blankets in the store-tent of Grayson & Guild, for nothing like a hotel and lodging house was known in the country outside of San Francisco.

The next afternoon arrived at Stanislaus City and became the guest of the surveyors & town projectors. I was so sore & stiff from my 3 days ride that I could hardly get out of the saddle. My horses were staked out and after supper we retired to our tent to sleep. Shortly after dark a heavy storm of rain and wind set in. About midnight I was awoke by the water coming under my blankets. The tent had been pitched in a depression of the ground which before morning was a pond. We at once got up to remove our blankets when a gust of wind blew the tent over and we were shelterless. We had to wrap our partially wet blankets around and sit on the ground the remainder of the night with our backs against a tree in the pouring rain. The incidents -of this night made me very much disgusted with camping out in the wet season. The next morning I was so lame and stiff from my ride and from the almost sleepless night I had passed that I could hardly stand on my feet. During the storm of the previous night one of my horses had broken his stake rope and taken himself-off. The other was not in a fit condition to be ridden back to the fort and I was not sorry when Mr. Stout ordered me to take passage with him to Sacramento via San Francisco.

There was a log cabin not far from Stanislaus City occupied by Mrs. Piles and her family. Mrs. Piles was a widow whose husband, Edward Piles,' had been murdered the previous summer by some Mexicans, near San Jose. Here my horse was left to be sent to Stockton, and the whole party embarked in a sailboat for San Francisco where we arrived in about a week.

The shores of the San Joaquin from the Stanislaus to Marsh's Landing. at its mouth (now Antioch) were a wilderness. Not a house did we pass the whole distance nor even see an Indian to break the monotony of the voyage.

We remained in San Francisco a few days where Mr. Stout and I took passage in the launch Dice mi Nana, Capt. Chas. H. Ross, and arrived at Sacramento about the middle of May.

On our passage up, we had to "tie up" one night & camp on the bank of Merritt's (now Steamboat) Slough. No description can do justice to the misery of a night thus passed in the warm months. Clouds of mosquitoes rendered sleep utterly out of the question, no matter how hard a man had worked all day at the oar or otherwise. The only way of getting through the night was to build a fire which could make as much smoke s possible and walk about until morning, flapping a handkerchief before the face.

The grand rush to California had now set in. Every imaginable kind of aft from a whale-boat up to the barque Whiten of 500 tons came up the river carrying passengers with their baggage. Boats were rowed up all the way from San Francisco. Many of these having on board incompetent pilots or no pilot at all would enter some one of the network of Sloughs, between the Sacramento and San Joaquin, and row about for days before they were extricated from the labyrinth.

During my absence from Sacramento great changes had taken place. The entire business portion of the community had removed from the fort to the river bank.

Hensley, Reading & Co. were the first in occupying a substantial two story frame building on the North comer of I and Front Streets. This building escaped the fires which devastated Sacramento & used as a fish market in later days was taken down within the past year. S. Norris had a store in Front bet. I & J with a grove of large oak trees in front; S. Brannan & Co. a one story frame building 30 ft by 85 South corner of J & Front; Priest, Lee & Co. a store partly frame and partly canvas, cor. J & 2nd. These were the leading business firms. Along the edge of the river from which the underbrush had been cleared was a continuous line of large vessels whose assorted cargoes were being rapidly disposed of at very large profits.

Structures composed of cotton cloth and strips of boards of all sizes were going up under the oak & sycamore trees in every direction. The price of lumber being $700.00 per thousand in large or small quantities that article had to be economized. Strips of board about 3 inches wide were sawn out and of these, placed edgewise, a skeleton or frame was constructed. Over this the white or blue cotton cloth was stretched, the door when there was one, being a curtain of the same material. The floor was the bare ground even in the more pretentious structures of Brannan & Co. and the pioneer stores. These shanties were built on lots no matter how low the ground. The warnings of some of the old pioneers not interested in Sacramento property that these lots would be from 8 to 10 feet under water in winter time were utterly unheeded. Had the flood of 1849-50 been as overwhelming as that of 1862, 1 do not hesitate to say that few would have been left to tell the tale.

William Daylor had been in the employ of Capt. Sutter in 1840. Since then he had been a neighbor & barring one or two interruptions, a close friend. Shortly after the new town was laid out, Daylor had loaned Sutter several thousand dollars without asking any security; for even then the latter had his periods of embarrassment. On the money being repaid the old gentleman to show his appreciation of what he considered a favor told Daylor to select some town lots & promised to execute a conveyance as soon as the choice was made.

Daylor not being skilled in the mysteries of town lot speculations declined this proposition being satisfied in his own mind that the first overflow of the river would sweep the whole town out of existence.

One firm and one alone, Smith, Bensley & Co., paid some attention to the warnings of "outsiders" and built their store, J Street between 2nd & 3rd, five feet above the ground with a board floor. The[y] found their profit January 8th 1850.

The Embarcadero Store (so called) of S. Brannan & Co. had two salesmen: J. Harris Trowbridge, who for some reason called himself John Harris, now living at Sing Sing Village N.Y., and W. L. Robertson, afterwards Supreme Judge of Oahu. The store at the fort was closed and Captain Sherwood went home to the East on a visit. Mr. Brannan having left for San Francisco, there to remain, and Mr. Stout being engaged mostly in outside speculations, I was appointed Cashier as well as bookkeeper.

The fourth of July, 1849, was celebrated in a grove of oaks on the very spot where now stands the State Capitol. The orators of the day were Wm. M. Gwin and, I think, Thos. Butler King.' These men had left friends & home and had kindly come to this far away region to represent us in Congress.

I remained with Brannan & Co. until November, when I left their employ and went into partnership with Mr. Daylor in keeping a store, mostly for the Indian trade - and a ferry where the road from Sacramento to the Southern mines was intersected by the Cosumnes river. Daylor and his brother-in-law, Jared Sheldon, called by the Californians Joaquin Sheldon, were joint owners of a 5 league Mexican grant called the Sheldon Grant and better known as the Daylor Ranch, 18 miles East from Sutter's Fort.

I here make a digression to say a few words concerning this Indian trade.

Before the discovery of the mines the foothills of the Sierra Nevada were thickly populated with various tribes of Digger Indians - the most harmless, inoffensive human beings that ever existed on the face of the earth. In the Summer months these Indians would come to the different Ranchos (by this word I mean farms of from 3 to 11 leagues of land in extent, and not its present signification, a board shanty on a 10 acre lot) and work for the proprietors in harvesting their crops of wheat. By this means the Rancheros near the foothills became well acquainted with all the chiefs and most of the members of these tribes. An Indian was glad to work in the harvest field with a sickle, for as much bull beef as he could eat, and a yard of cotton cloth for a week's wages.

When the great discovery took place, P. B. Reading, John Bidwell, Nye, Foster, Covillaud, Sinclair, Daylor, Sheldon, McCoon, the Murphys & some others hastened to the foot hills with droves of cattle and, in course of time, supplies of flour, hard bread, sugar, raisins, beads, dry goods & clothing; spirituous liquors being by common consent rigidly taboo. The Indians, who, up to this time, had subsisted on acorns, grasshoppers, grass-seeds & sometimes fish & a few wild fowl, the males & children going entirely naked the year round, worked with great energy to acquire the heretofore unheard of luxuries supplied by the traders. At first there was no weighing or measuring either of goods or gold; so much beef or flour for as much gold as could be grasped in the hand. As scales were introduced, sugar, raisins, beads or silver dollars were put in one scale & balanced by gold in the other. Few persons now living have any idea of the enormous quantity of gold taken out in the summer of 1848 before the advent of white strangers. In the "dry diggings" where no water was required, the gold being found on and near the surface, the ground was worked over with knives, spoons, pieces of iron & pointed sticks. On the "bars" and other places where dirt had to be washed, the Indians used baskets made by the squaws which were perfectly water tight. Most of the ground, thus worked in 1848, was mined over & over again as new methods of extracting gold were discovered, from 5 to 7 times and finally abandoned to Chinamen. As new comers made their appearance and competition in trade commenced, the Indians were freely supplied with liquor by the newly-established white traders and of course became greatly demoralized. Their early protectors, the rancheros, left the mines in disgust; the poor aborigines were abandoned to the mercy of a number of semi-barbarous white men, and died and were killed off with frightful rapidity. The first to commit outrages upon them were emigrants from Oregon, who with the massacre of the Whitman family by the Indians of that territory fresh in their minds, fully carried out the proposition that Indians had no rights whatever as human beings. For accounts of some of the outrages committed upon them I refer to early numbers of the Placer Times and to an article written by Ross Browne in Harpers Magazine for August, 1861. Instances were by no means rare where an Indian, working a piece of land and hesitating about giving it up at the command of some white ruffian, [was] ruthlessly shot down and his body tossed aside to be burned or buried by the members of his tribe.

The trade of my partner & myself was mostly confined to those Indians who lived in rancherias or villages on the Daylor & Sheldon ranch. These Indians would make excursions to the mines in bands. In a few weeks they would return, having been more or less successful in mining but always bringing back more or less gold. On their return the first call was invariably for beef. A bull or torune (Stag) was driven up to the villages killed, and handed over to the purchasers who consumed every particle of the animal except hide, horns & bones. They would eat to repletion, lie down to sleep and, on wakinl4 up again surfeit themselves. This would be continued until the meat and all the insides were eaten & the bones picked clean. They would then visit the store, accompanied by the squaws & purchase Zarapes (Mexican blankets), dry goods, beads, sugar, raisins & sweetmeats. If, during their stay in the rancheria, some distinguished member of the tribe died, which frequently happened, the corpse was placed upon a funeral pyre and into the fire went all the previous purchases of the tribe as well as all property owned by the deceased down to his dogs, the yelps of these latter joined to the howling of the Indians making a fearful noise. The dog part of the sacrifice was looked upon by the whites on the ranch with indifference but in one case my partner stopped them when about to hoist into the fire an Indian pony.

In trading with Indians it was considered legitimate (even in the stores at the fort) to have two sets of weights. The Indian ounce weight was equal to two ounces standard and so on up.

The roads in the Winter of 1849 & 50 were nearly as bad as in that of 1848 & 49. We paid $800 for one 8 mule load from Sacramento 18 miles and then found that the goods sufficient to meet the demand could not be hauled at any price.

On the 31st of October 1850 Mr. Daylor died of Cholera. The few remaining Indians left their villages & never returned. Daylor's brother-in-law, Sheldon, was appointed administrator and Mrs. Daylor went to Sacramento to reside. As Sheldon lived some distance off, he placed me in charge of the ranch & personal property consisting of several thousand head of wild cattle between one & two hundred mustang brood mares, riding horses, hogs etc. Daylor left no children.

I married Mrs. Daylor April 22nd 1851. She was born in Edgar County, Illinois, January 28th 1830. Her maiden name was Sarah Rhoads. She is the daughter of Thomas Rhoads, a native of Kentucky, who came to California with his wife, 7 sons & 5 daughters, 4 of the latter unmarried, October 5th 1846. The eldest single daughter in 1846 married Sebastian Keyser, who had some interest in & lived upon Johnson's Ranch, Bear River. The second daughter married Wm. Daylor in March 1847. The third married Jared Sheldon in April 1847. The youngest daughter became the wife of John Clawson of Salt Lake City, UT. S. Keyser was employed as ferryman by Daylor and myself and was drowned by the by the swamping of his boat January 1850. His widow is living at Kingston, Fresno County. Jared Sheldon, - known to the native Californians as Joaquin Sheldon - was killed in a fracas with some miners in July, 1851, leaving a widow who is living near the Daylor Ranch, and two children,' William, born February, 1948, & Catharine, born June 28th 1851, now living with their mother.

Of Mr. Rhoads' sons, John, the eldest, died in December, 1866; Daniel, William B. & Henry C., [live] in Fresno County; Thomas was drowned crossing the "plains", 1852; Caleb is in Utah Territory. Mr. Rhoads died in- Utah Territory in 1869, 77 years of age, never having suffered a day's sickness, except I attack of ague, with every tooth in his head and every tooth sound.

Since my marriage I have lived on the ranch and at intervals in Sacramento. I have 7 children living and have buried 5, all of whom died under 4 years of age. My children are Wm. R., born in Sacramento City, March 31, 1852; Emma born in Sacramento City, November 26th, 1853; Thomas Minturn, born Daylor's Ranch, August 15th, 1856; George, Daylor Ranch, October 8th, 1858; John Francis, June 1st, 1862; Frederick, May 9th, 1866, and Walter, January 15th, 1868 all born at Daylor Ranch.

There, gentlemen, is what I suppose your circular calls for. If the papper I have written out or any part of it is suitable as a contribution to your forthcoming work it is at your service and I will furnish you at another time with a few further reminiscences of the early pioneers with whom it was my fortune to be brought in contact; if not so suited, please return the manuscript.

Of one thing you may rest assured, and that is the literal truth of everything I five stated of my own knowledge without the slightest embellishment. In my own mind I am perfectly satisfied of the correctness of everything I have stated on information. There is a hastily written sketch of the early history of Sutter's fort & Sacramento and the first rush to California, in the Sacramento City Directory for 1854, by Dr. John F. Morse... of San Francisco, which contains much valuable information.

If you can persuade philosopher C. E. Pickett of your city to forego for a time his schemes of reform and the amelioration of the human race there is no man in the state better qualified as a contributor to your work.

There is a man named Edward Robinson (mentioned in my former communication) who came to California before 1830. He lives in the Canada do los Oso near Gilroy. If you could have an interview with him he could tell a great deal concerning the early history of the state, he being a very intelligent man.

Shortly after Marshall's discovery two Mormons - Wilford & another - on their way from "the mill" to Sutter's Fort were overtaken by sunset about 25 miles short of their destination. They shot a deer and sought the nearest point on the South Fork of the American river, to camp for the night. After descending the steep bank or bluff which rose from the stream, they came upon a flat or interval some 4 or 5 acres in extent mostly overgrown with small shrubbery where they encamped. After supper and while some light still remained one of the men proposed to prospect the ground. Removing the top layer of earth from a spot near the waters edge they came upon a stratum of gravel rich in gold. The next day they made their way to the fort and informed Samuel Brannan of their discovery - Brannan being a sort of deputy Pontifex Maximus of the Morrnon church. Mr. Brannan repaired to the spot, set up a claim of 160 acres of land under the preemption laws of the United States (a claim for 11 leagues under the colonization laws of Mexico would have been equally valid) and demanded a royalty of one third of all the gold mined within the boundaries of his' claim. This was unhesitatingly paid by the Mormons, who were the first miners, but, as "outsiders" began to arrive, Brannan's right to his rovalty was questioned & was soon abandoned; not however until he had collected some thousands of dollars. This "raise" enabled Brannan to form a partnership with Mellus & Howard and laid the foundation of his large fortune.

The bar was called Mormon Island, well known & widely celebrated for the large quantity of gold it yielded in 1848 & 49. The town of that name in Sacramento County is built upon the bluff above the flat. The bar has been repeatedly worked over; the last vestige of it was long since washed away by the river, and nothing but a bank of white sand remains in its place.

I do not vouch for the truth of that part of the story pertaining to Samuel Brannan, but when I first came to New Helvetia it was the subject of frequent conversation and I never heard it denied then or since.

Appendix

PIONEER CRIMINAL TRIAL IN SACRAMENTO

Following is the text of Grimshaw's letter to the Sacramento Union, published in its issue for May 14, 1855. The sketch to which Grimshaw refers, Sacramento in 1849, was written by Baron Vieux, and is primarily a list of names of citizens and business establishments of the early days.

Messrs. Editors. –

The sketch in your paper of "Sacramento in 1849," by "the Baron" brings to mind the following reminiscence of the first criminal trial held within the walls of Sutter's Fort, by an eye witness.

In the fall of 1848, C. E. Pickett, then a merchant, having his store in the Northeast angle of Sutter's Fort, had rented a portion of the fort including the Northwest bastion, where there was formerly a distillery. The use of this bastion or the ground adjoining was also claimed by a man named Alderman. Pickett and Alderman had an altercation which resulted in the former shooting the latter dead.

The first or head Alcalde under the Mexican law, Franklin Bates, was requested to place Pickett under arrest. He at once resigned his office. The second Alcalde, John S. Fowler, was then waited upon. He also resigned. Samuel Brannan, Esq., then doing business in the adobe building east of the fort, took the affair in hand, and called upon the residents of the fort to hold a meeting at his store, to enquire into the matter. The meeting assembled and proceeded to elect an Alcalde; Mr. Brannan was chosen and accepted the office. Then came the office of Prosecuting Attorney. One man would be nominated, decline and propose someone else. The one proposed would in his turn decline and name another. When the appointment had gone the round of the meeting without success, Mr. Brannan accepted of this office also. A. M. Tanner was elected Sheriff for the occasion, and notified Pickett to appear and take his trial the ensuing evening. The trial took place in a room in the western side of the fort, where Pickett accordingly presented himself at the appointed time. A jury was empanneled, among whom were John Sinclair, (then residing on what is called Norris Ranch), foreman; Capt. Sutter, Capt. Wm. H. Warner, who afterwards surveyed the site for Sacramento City, Wm. Petit, a merchant, and others whom the writer does not recollect. H. A. Schoolcraft defended Mr. Pickett. Before proceeding to trial some one proposed that the defendant should surrender any arms he might have about him. Pickett accordingly "laid down his arms," consisting of a revolver and bowie knife, upon the table before him. During the trial, the judge, jury, defendant and spectators had their brandy and water at pleasure. When the question arose whether cigars could be introduced into court the judge settled the matter by saying that as the ladies of California used tobacco, it could not be out of place anywhere. Cigars were accordingly brought in for such as wanted them.

The trial was conducted upon the broadest principles of equity, the spectators making motions and occasionally questioning a witness. - The foreman, enveloped in the folds of his serape, lay back in an angle of the walls of the room during a portion of the trial - fast asleep!

The evidence went to show that Pickett had erected a gate across a sort of lane leading to the bastion. This gate Alderman chopped down with an ax. Pickett sent a man to build another, and mounted guard near him with a double-barreled shot gun. Alderman made his appearance, brandished an ax, and told Pickett to leave. Pickett commenced retreating backward, his opponent advancing, and warned Alderman to stop. Alderman advanced and Pickett retreated until his back was against the wall of the bastion. He then leveled his gun, fired, and Alderman dropped dead. The evidence of some men who had known the deceased in Oregon proved him to be a lawless, turbulent man. As this was being given Capt. Sutter arose, saying, in language with more of an accent than he now uses, "Gentlemen, the man is dead; I cannot hear evil spoken of him," and started to leave the room, and it was only at the peremtory command of the judge that he took his seat.

When the evidence was finished the judge began a plea for the prosecution.

'Hold on, Brannan," said Pickett, "you are the judge."

"I know it," said Brannan, "but I am prosecuting attorney, too."

"All right," said Pickett, and the speech was concluded.

Pickett then arose, finished his glass of brandy and water, and told the jury he was going to "open on them." He made a most excellent defence.