American Mechanical Engineer

![]()

(Webpage still under construction)

Robert E. Grimshaw developed a distinguished professional career as a mechanical engineer in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He published numerous technical books and was on the faculty of New York University, City College of New York and Rutgers University. He was also a participant in the founding of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME.)

Photographs of Robert E. Grimshaw

Advertisement for Professional Services

Co-Founder of American Society of Mechanical Engineers

First Work Sample: Lessons in Personal Efficiency

Second Work Sample: Fifty Years Hence, or What May Be in 1943

World War II Report of Captain William Stelling, Robert’s Grandson

| Webpage Credits |

Thanks go to Hilary Tulloch for providing family history records that include information on Robert Grimshaw. Also to Dana McKay for providing photographs of Robert. Finally, thanks to Mike Stelling for Captain William Stelling’s report from World War II, which appears at the end of this webpage.

| Photos of Robert E. Grimshaw |

Dana McKay is in possession of several photos of Robert Grimshaw, two of which are shown below. These two were selected to depict Robert across the span of his life – the first was taken when he was age 18, and the second at age 80. Robert apparently lived for at least another 10 years after the second photo was taken.

Figure 1. Robert E. Grimshaw at age 18. This photo was signed by Robert on August 20, 1868; the signature appears at the top of this webpage.

Figure 2. Robert Grimshaw in 1930 (age 80).

| Biography |

A brief biography of Robert was published in the Who's Who in New Jersey1 in 1939, while he was still living, as shown below.

GRIMSHAW, Robert, engineer; b. Phila., Pa., Jan. 25, 1850; s. William and Marie Caroline (Delacroix) G.; prep. edu., Taylor's Acad., Wilmington, Del.; grad. Andalusia Coll., Pa., 1869; studied under Profs. Alexander and Guyot, Princeton, and in Paris, France; Ph.D.; m. Margaret Morton Dillon, of Wilmington, Del., Apr. 2, 1872 (died 1877); children - Charlotte (Mrs. Malcolm MacLear), Mary Morton (Mrs. Cornelius B. Hite), Edith Dillon (Mrs. Adolf Stelling); m. 2d. Marta Sharstein, of Kappeln, Schleswig Holstein, Germany, May 16, 1914. Began practice 1873; was mem. faculty New York U., Coll. City of N.Y. and Rutgers Univ.; served as consulting engr. for U.S. Govt., and various European govts. A founder Am. Soc. Mech. Engrs.; corr. sec. Polytechnic Soc.; ex-pres. James Watt Association Stationary Engineers; member National Institute of Social Sciences. Founder of "Blindaid," furnishing Braille printed matter. Republican. Episcopalian. Odd Fellow. Author: Why Manufacturers Lose Money, 1922; The Modern Foreman, 1923; Shop Kinks (6th edit.); Machine Shop Chat, 1923; The Locomotive Catechism (30th edit.), 1923; also many other tech. works in English, German and French. Home: 321 Sylvan Av., Leonia, N.J.

| Advertisement for Professional Services |

Robert’s professional interests and capabilities were well described in his own advertisement for his consulting services. An example is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Robert Grimshaw’s advertisement for consulting services. This example appeared in his book, "Fifty Years Hence" (described further down on this webpage,) which was published in 1892, after Robert had been in practice for nearly 20 years.

Robert was the youngest son (one of two children) of William Grimshaw by his second wife, Marie Caroline Delacroix. William died before Robert was two years old, and records indicate that Robert may have been raised by his half-sister, Charlotte. William Grimshaw, noted historian and emigrant to Philadelphia from Ireland, was in the "Irish" line of Grimshaws and is the subject of a companion webpage.

Robert had three daughters by his first wife, Margaret Morton Dillon, before her untimely death just a few days after the birth of their third child. Robert’s second marriage, to Marta Sharstein in Germany, occurred considerably later in life, and there were apparently no children to that marriage. A descendant chart for Robert down through his grandchildren is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Descendant chart of Robert Grimshaw through his grandchildren. Note that the date of his wife’s death was a mere nine days after the birth of the youngest child, Edith Dillon Grimshaw. Thanks again to Hilary Tulloch for providing this information.

1. Robert GRIMSHAW

b.. 25 Jan 1850, USA, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; occ. Engineer; edu. Taylor's Academy, Wilmington, Delaware; Andalusia Coll., Pennsylvania; rel. Episcopalian; d.. aft 1940

& Margaret Morton DILLON

b.. 1 Aug 1847; d.. 10 Feb 1877, USA, Philadelphia; m.. 2 Apr 1872, USA, Delaware, Wilmington

|-----2. Charlotte GRIMSHAW

|-----b.. 3 Mar 1873, USA, New Jersey, South Orange

|-----& Malcolm MacCLEAR

|-----b.. 5 Feb 1872, USA, Delaware, Wilmington; d.. May 1912, USA, New Jersey, Newark; m.. 19 May 1896, USA, New Jersey, Tenafly

|-----|-----3. Malcolm McCLEAR

|-----|-----b.. 29 Jul 1898, USA, New Jersey, Chatham; d.. Jun 1986, USA, Florida, Hillsborough County, Tampa

|-----|-----3. Mary Morton MacCLEAR

|-----|-----b.. 10 Jun 1900, USA, New Jersey, Newark; d.. Feb 1981, USA, Connecticut, Fairfield County, Bridgeport

|-----|-----3. Helen MacCLEAR

|-----|-----b.. 4 Mar 1902, USA, New Jersey, Newark; d.. 27 Dec 1905, USA, New Jersey, Newark

|-----|-----3. Charlotte Grimshaw MacCLEAR

|-----|-----b.. 30 Jul 1903, USA, New Jersey, Newark; d.. Mar 1986, USA, Connecticut, Fairfield County, Bridgeport

|-----|-----3. Margaret Lea MacCLEAR

|-----|-----b.. 7 Jun 1906, USA, New Jersey, Newark

|-----2. Mary Morton GRIMSHAW

|-----b.. 25 Sep 1874, USA, Delaware, Wilmington

|-----& Cornelius B. HITE

|-----2. Edith Dillon GRIMSHAW

|-----b.. 1 Feb 1877, USA, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; d.. bef 1972, USA

|-----& Adolf Carl Henry Peter STELLING

|-----b.. 19 Mar 1864, Germany, Prussia, Harburg; m.. 19 Jun 1899, Germany, Dresden

|-----|-----3. Emilie Margaretha STELLING

|-----|-----b.. 22 Mar 1902, Germany, Bremerhaven; d.. ca 1973, USA

|-----|-----& Robert Paul McGEEHAN

|-----|-----3. Adolf Carl (Carl) STELLING*

|-----|-----b.. 31 May 1903, USA, New Jersey, Weehawken; d.. Mar 1979

|-----|-----& UNNAMED

|-----|-----3. Adolf Carl (Carl) STELLING*

|-----|-----b.. 31 May 1903, USA, New Jersey, Weehawken; d.. Mar 1979

|-----|-----& Francesca

|-----|-----3. John Morton (Morton) STELLING

|-----|-----b.. 5 Mar 1907, USA, New Jersey, Weehawken; d.. Sep 1985, USA, Florida, Hillsborough County, Riverview

|-----|-----3. William Taylor (Bill) STELLING

|-----|-----b.. 7 Mar 1914, USA, New Jersey, Weehawken; d.. 10 Aug 1998, USA, Florida, Brevard County, Titusville

|-----|-----& Karin PETERLEUSCH

|-----|-----d.. bef 2001

|-----|-----|-----4. Michael (Mike) STELLING

|-----|-----|-----b.. 1954

Thirty-year-old Robert Grimshaw was present at the founding meeting of ASME in 1880. ASME is one of the larger professional societies in the world and probably the largest for the field of mechanical engineering. ASME’s website provides the following overview information about the organization, including its mission and vision.

The 125,000-member ASME International is a worldwide engineering society. It conducts one of the world's largest technical publishing operations, holds some 30 technical conferences and 200 professional development courses each year, and sets many industrial and manufacturing standards. Founded in 1880 as the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, today ASME International is a nonprofit educational and technical organization serving a worldwide membership.

Vision: To be the premier organization for promoting the art, science and practice of mechanical engineering throughout the world.

Mission: To promote and enhance the technical competency and professional well-being of our members, and through quality programs and activities in mechanical engineering, better enable its practitioners to contribute to the well-being of humankind.

http://www.asme.org/about/

The founding of ASME is described as shown below on its website; Robert Grimshaw was one of about 30 who attended the initial meeting. His role in the following weeks and months in bringing the organization into being is not known.

ASME International was founded in 1880 by prominent mechanical engineers, led by Alexander Lyman Holley (1832-1882), Henry Rossiter Worthington (1817-1880), and John Edson Sweet (1832-1916). Holley chaired the first meeting, which was held in the New York editorial offices of the American Machinist on February 16 with thirty in attendance. On April 7 a formal organizational meeting was held at Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, New Jersey, with about eighty engineers--industrialists, educators, technical journalists, designers, shipbuilders, military engineers, and inventors.

http://www.asme.org/history/asmehist.html

Who are ASME's Founders?

Alexander Lyman Holley (1832-1882), Henry Rossiter Worthington (1817-1880), and John Edson Sweet (1832-1916) are Honorary Members among the founders and can be considered the foremost organizers.

Samuel S. Webber acted as secretary. Eckley B. Coxe, General Quincy Gillmore, Jackson Bailey, Professor W.P. Trowbridge, and M.N. Forney are among the lesser known today who also worked on organizing committees. Erasmus D. Leavitt and Charles T. Porter are among the better known. Charles W. Copeland suggested the name of the society.

"Thirty of the most prominent men in American mechanical industry attended that first meeting of ASME founders in the New York editorial offices of American Machinist on 16 February 1880. They chose as chairman the brilliant consultant to the American Bessemer Steel Association, Alexander Lyman Holley, and, characteristically, he provided a focus for the gathering profession and the advantages to be derived from association." (A Centennial History of ASME, by Bruce Sinclair, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980)

On April 7 a formal organizational meeting was held at Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, New Jersey, with about 80 engineers. The first annual meeting was held in early November 1880. Robert H. Thurston was the first president.

Who were the others in attendance on February 16?

Stephen W. Baldwin, George A. Barnard, William Lee Church, George M. Copeland, J.S. Coon, A.B. Couch, Charles E. Emery, John Fish, Robert Grimshaw, F.F. Hemenway, D.S. Hines, Wiliam H. Hoffman, H.T.C. Kraus, Lewis F. Lyne, C.C. Newton, W.H. Odell, T.R. Pickering, Frank C. Smith, Egbert P. Watson, Samuel Webber, and Albert R. Wolff.

http://www.asme.org/history/founders.html

| Publications List of Robert E. Grimshaw |

As an integral part of his very active and prolific professional career, Robert published many technical books over the span of nearly 50 years. A large number of these books, in turn, were published in numerous editions. In addition, he published books on foreign languages (to the U.S.), on German and French.

Because Robert’s publications were so numerous and varied, and were published in many editions, it would be a daunting task to compile a complete bibliography. This task is not attempted here, but the online catalogues of a number of libraries were surveyed to capture at least the majority of Robert’s extensive works. The online catalogues surveyed were for the following libraries and organizations: Library of Congress, New York Public Library, British Library (London), Harvard Library, California University Library System (MELVYL), The University of Texas, the University of Chicago and the University of Wisconsin.

The resulting list is shown below with the approximate date of initial publication. Figure 4, below the list, shows an advertisement for his "catechisms" as published in one of his books.

|

The polytechnic review |

1876 |

|

Saws: the history, development, action, classification and comparison of saws of all kinds. With appendices concerning the details of manufacture, setting, swaging, gumming, filing, etc |

1880 |

|

The sugar beet. Devoted to the cultivation and utilization of the sugar beet |

1880 |

|

The miller, millwright, and millfurnisher: a practical treatise |

1882 |

|

Hints on house building : some desultory notes, in popular form |

1887 |

|

Preparing for indication: practical hints, the result of twenty-three years' experience with the steam engine indicator |

1888 |

|

The steam-boiler catechism. A practical book for steam engineers, and for firemen, owners and makers of boilers of any kind |

1888 |

|

The pump catechism : a practical help to runners, owners and makers of pumps of any kind; covering the theory and practice of designing, constructing, erecting, connecting and adjusting |

1889 |

|

Hints to power users. Plain, practical pointers, free from high science, and intended for the man who pays the bills |

1891 |

|

Modern workshop hints, describing unusual and rapid ways of doing work from the latest and best American and other machine shop practice, etc. |

1891 |

|

The engine runner's catechism: telling how to erect, adjust, and run the principal steam engines in use in the United States, being a sequel to the steam engine catechism |

1891 |

|

The practical catechism : a collection of questions on technical subjects, by manufacturers and others, and of answers thereto |

1891 |

|

Fifty years hence, or, What may be in 1943 : a prophecy supposed to be based on scientific deductions by an improved graphical method |

1892 |

|

Record of scientific progress for the year 1891, exhibiting the most important discoveries and improvements in all the branched of engineering, architecture and building, mining and metallurgy, the mechanic arts |

1892 |

|

Engine-room chat |

1893 |

|

Nystrom's pocket-book of mechanics and engineering |

1895 |

|

Shop kinks and machine-shop chat: a series of practical paragraphs showing special ways of doing work better, more cheaply and more rapidly than usual, etc. |

1896 |

|

The steam engine catechism : a series of direct practical answers to direct practical questions, mainly intended for young engineers, and for examination questions |

1897 |

|

Apollo's System des physischen Unterrichts für das Haus, zeigend wie jeder Muskel des Körpers entwickelt und Gesundheit, Stärke und Widerstandsfähigkeit wiederlangt werden können |

1902 |

|

French genders. Rules and exceptions |

1902 |

|

German genders. Rules and exceptions |

1902 |

|

Leitfaden für das isometrische Skizzieren und die Projektionen in den schiefen oder sogenannten Kavalier-Perspektiven u.s.w. mit besonderem Bezug auf die isometrischen Skizzen-Blöcke (D.R.G.-M.) des Ingenieurs |

1902 |

|

The Fourth of July |

1903 |

|

Werkstatt-Betrieb und -Organisation, mit besonderem Bezug auf Werkstatt-Buchführung, von Dr. phil. Robert Grimshaw ... Mit dreihundertfünfundfünfzig Formularen und Diagrammen Meistens aus der Praxis berühmter amerikanischer Firmen |

1903 |

|

Hints to inventors |

1907 |

|

Lessons in personal efficiency |

1918 |

|

The modern foreman |

1921 |

|

Why manufacturers lose money |

1924 |

Figure 4. Advertisement for Robert Grimshaw’s "Catechisms." The topics included a "practical" catechism and one each on steam engines, pumps and locomotives. This ad appeared in Robert’s "Fifty Years Hence," which was published in 1892 and is described in more detail further down on this webpage.

| First Work Sample: Lessons in Personal Efficiency |

Most of Robert’s publications are highly technical in nature. Two, however, stand out from the rest in seeming to offer insight into his personality and world view. The first one described here, "Lessons in Personal Efficiency," was published in 1920, when Robert had developed his career for nearly 50 years. The second one, "Fifty Years Hence, or What May Be in 1943," was published in 1892, when his career had been established for about 20 years. It is described in the next section of this webpage.

The table of contents of "Lessons in Personal Efficiency" reveals the broad range of Robert’s interests in human behavior and discipline from an engineer’s perspective – attention, perception, standards, planning, habits, fatigue, memory, reasoning, the Will, and the ethical topics of loyalty and cooperation. A sample of this fascinating work, reflecting a thoroughly Modern world view, is provided below – the first two Lessons.

With the implicit values indicated, Robert may have felt quite comfortable with a spouse from Germany, a country with a strong reputation for high efficiency!

PREFACE

There is little need for any more preface than merely to state that from the very beginning the publication of my lectures has been called for by those who heard them at the New York University and elsewhere. As they were very largely impromptu, and as the mass of notes from which they were delivered grew with each repetition, their publication as delivered has been impossible, but this resume may serve as a useful reminder to those who heard the lectures, and a thinking point for those to whom I have not had the advantage of speaking.

ROBERT GRIMSHAW

717 W. 177th St.,

New York, January, 1918.

CONTENTS

LESSON PAGE

I. INTRODUCTION 1

II. EXAMPLES OF EFFICIENCY 13

III. FORCES – ATTENTION 30

IV. ATTENTION 43

V. PERCEPTION 56

VI. RECORDS AND STANDARDS 71

VII. PLANNING 85

VIII. ENVIRONMENT AND HABIT 101

IX. TIME – FATIGUE 115

X. MEMORY 13 I

XI. REASONING, ETC. 159

XII. THE WILL 172

XIII. LOYALTY AND COOPERATION 179

XIV. SHORTCUTS 194

LESSONS

IN PERSONAL EFFICIENCY

LESSON I

INTRODUCTION

The word "efficiency." In the beginning let us be clear about what the word means. The man who would start out studying about arson, under the impression that it meant highway robbery, or housebreaking, would not progress very far on the road to knowledge of ltis subject.

"Efficiency" is a quality of mind, or of body, producing, or capable of producing, maximum result with a given effort, or a given result with minimum effort; akin to buying a maximum amount of goods with a given sum of money, or a given amount with minimum outlay.

Strenuousness vs. Efficiency. Efficiency is not only entirely unconnected with strenuousness, which implies a strain, but in fact is diametrically opposed thereto. The elephant is less efficient, although much more powerful, than the horse. Foreign missions are much less efficient than domestic, because they produce comparatively little result for a given outlay of cash, human life and effort.

Effectiveness vs. Efficiency. Efficiency is not effectiveness. A thing may be wonderfully effective or efficacious, yet not efficient. A medicine which is too powerful may be effective, but not efficient, because it does not "reduce the desired result with a minimum of effort." Taking a line of trenches at immense and needless cost of life and munitions is "effective" in clearing out the enemy – but lamentably inefficient, because the desired result is not attained with minimum effort. One may remove a rock from the road which it blocks, by pulling it out of the way on a sled; it would be more efficient to use rollers, or explode a dynamite cartridge under it.

Capacity vs. Efficiency. Defined scientifically, we have capacity as "ability to receive, understand or accomplish; adaptedness to do; productive power;" whereas efficiency ("duty," the professional engineer calls it) is "the ratio of useful work, or of effect produced, to the energy expended or outlay made in producing it."

More concretely put:-

Capacity is ability to make or to do at a certain rate per time unit, as to turn table-legs, reap wheat, haul coal, deliver letters, make out bills, at a certain speed.

Inefficiency. To carry a loaded wheelbarrow on the head, as the negroes in Jamaica and the Italian women in New York do with ordinary loads, would be inefficient; so would letting its axle bearings get rusty, and pushing it.

Mental efficiency implies well-trained, well-exercised, well-balanced, well-coordinated brain, fed in proper quantity with rich red blood, and subordinated to a calm and cheerful soul and spirit. The mentally efficient man can handle ordinary brain problems at a reasonable rate, without effort, during ordinary working periods; and in emergency draw on his reserve mental forces so as to prolong and intensify his mental activity, without endangering his sanity or equanimity. As a rule, mental efficiency calls for a healthy body. "Mens sana in corpore sano" is a valuable possession, well worth striving for. The study of efficiency will help attain, keep and enjoy, both factors.

Mental efficiency is improved in the same way as physical – by systematic practise based on correct principles. But there is no way of improving general mental efficiency. One may improve the memory, for instance; but that does not increase the general mental power. Each mind faculty must be strengthened, and the manner of its application bettered; just as anyone set of muscles can be strengthened, and the manner of their application improved – each set for itself. Thus, improvement of memory does not imply betterment of perception or reasoning; nor is there any system of mental education which will develop memory, perception and reasoning power at the same time.

Moral efficiency means more than mere adherence to commandments. It implies victory over self. It goes beyond the Decalog.

Muscular efficiency has to do wish all the muscles, in connection with the framework with which they act. It is inconsistent with either much fat or a very lean bodily condition. It is essential that every man keep his muscles strong, uniformly developed and under control of brain and nerves, that he may serve and protect himself, his family and his country.

The muscles may be kept supple and elastic long after the bones are brittle; hence old people should avoid exercises or activities which might risk a heavy fall. Outdoor exercise is the best method of keeping the muscles efficient, .and subservient to the will; but t11ere are many "home" exercises which call for no apparatus, and keep the waist line down and the muscle efficiency high. While not every elderly man can be a Muldoon, all may profit by his teachings.

Physical efficiency calls for more than mere muscular strength or agility:- so-called "fitness." It refers to digestion and every physical function. It demands good teeth, stomach, lungs, heart, muscles, and all other parts of our complex and correlated or coordinated system. It tends to assist the attainment of a good condition of the entire physical system.

Commercial efficiency consists in getting a given profit with least possible expenditure of work, capital and time, and least risk. It may come from anyone of the following factors;-

1. Organizing.

2. Planning.

3. Buying.

4. Selling;

or from a combination of any two or more of these.

Personal efficiency may be either moral, mental or physical. To attain a high standard in all three lines is difficult-but this very fact should inspire us all with the desire to commence early and strive long and hard to raise soul, mind and body to the highest level that time and opportunity permit.

Corporative efficiency (i.e., the efficiency of a corporation) depends not only on that of the individual units, but also on their perfect co-ordination. Thus our national government is far from efficient, because its units are changed too often and do not work in harmony with each other. There is duplication of activities in some cases, entire neglect of important functions in others. Our States have conflicting laws – for instance concerning marriage, divorce, inheritance, etc.

Latent efficiency, – that which lies dormant until wakened by some outside influence – probably exists in every normal person; indeed may be uncovered from the cloud which obscures it, in many instances considered as abnormal or only subnormal – as witness the development of the mind and body in "defective" children, caused by simply removing adenoids.

Active efficiency bears the same relation to passive as a machine gun in action to one all ready for service. It is the brain supplied with good red blood, trained to logica1 reasoning, and capable of retaining impressions, compared with one capable but untaught.

Passive efficiency is that which, while existing, requires the application of some external force to utilize it – for instance in a steam engine, a cannon or a bow. It cannot put itself in action, as can the mind.

Efficiency is usually only relative. The standard of attainment is generally capable of being raised – in the case of persons by effort from within; in that of the brute animals and of things, by forces acting from without. Thus the memory may be wonderfully improved; the range of cannon and the speed of race-horses has been raised by human effort acting along lines of principles based on records.

Absolute efficiency does not exist in things human. But the higher we aim, the more likely we are to attain a high degree of efficiency – always providing that we follow principles which have been shown to lead to lead to higher and higher results.

Regular efficiency is that which has no seasons; no days nor nights; but goes on from time to time at the same rate – whether steady or regularly increasing. The essential is that it be unceasing and unremitting. The mill-stream which at one season overflows its banks and drowns the wheel, at another has to be helped out by a steam engine, may be powerful on an average; but cannot be said to be regularly or even generally efficient.

Symmetrical efficiency may be compared to that of a symmetrically developed human body, where there is absolute beauty and proportion among all the members – not as with the blacksmith, whose arms are unduly developed as compared with his legs.

Automatic efficiency is that kind which, once attained, goes on for itself without new guidance or impulse. It may be carried so far that it is inherited – for instance in the trotting horse. His gait is not natural but an improvement on that which he inherits – but the offspring of several generations of trotters have been known to trot without instruction.

Scientific efficiency is a term usually applied to the state resulting from organization and special investigation and research, coupled with vocational guidance. It is most often applied to manufacturing conditions. The term, as well as the science and art to which it refers, have been much used by both fakers and honest incompetents, particularly in America. The father of this science was the late Frederick W. Taylor. He and his disciples have done much to improve American efficiency and increase the well-being of American employers and workers.

Efficiency of production enables a manufacturing plant, for example, to produce at minimum cost for materials, labor, and general expenses; to enlarge or diminish its output according to the demand of the product; and to keep plant, organization as such, and personnel, unimpaired in both slack and rush seasons and periods.

Efficiency of supply refers to utilization of the time, money, muscular energy, etc., at our disposal, and which we cannot increase. In money matters it spells thrift, in contradiction to mere earning power. In the matter of time it means no unnecessary stoppages – no retracing of steps; no useless or hindering movements; so that we live to best advantage with the fixed income which all have from birth to death, of twenty-four hours a day.

Efficiency of quality implies getting out of soil, fibre, or other source, the best practicable and attainable quality of product; distilling the best elements and discarding the less valuable; raising the standard of purity and of excellence – but irrespective of the time, effort and money expended in attaining mere quality. It is usually incompatible with efficiency of supply.

Efficiency of use refers to the manner of utilizing one's supply of material, labor, time, money, physical or mental capability. Just as at table one man can eat a fish or a crab, and leave but little unedible material on his plate, while another will get only half the meat so one man shows efficiency of use will live better on $2,000 a year than another on $2,500 or even $3,000. Efficiency of use comes partly by nature, partly by training. It may be entirely distinct from stinginess on the one hand, extravagance on the other.

Efficiency of assignment differs from that of supply, quality or use; being a compound ratio showing the proportions between

1. The value of the product in a given unit of time, and

2. The standard value of the product.

The carpenter who in picking up or straightening a nail spends time worth more than the nail, shows inefficiency of assignment – unless it is the last nail available. The mechanic who from pure laziness uses a monkey-wrench as a hammer shows inefficiency of assignment, as the wrench not only does not do the work of the hammer well, but is liable to be sprung by the rough usage. But if it were a question of spoiling a good wrench, sooner than delaying a repair that might cause damage, or of losing more than its value in time going for or waiting for a hammer – then the efficiency of assignment would be good.

Partial efficiency might be compared with partial good health or partial commercial solvency. Games at home and outdoor exercises should be chosen which will develop the entire body; courses of study selected which, while specialized to conform with one's occupation or personal bent, yet leave no mental faculty absolutely undeveloped. No muscle, moral fibre, or mental faculty should be allowed to get atrophied,

Compound or resultant efficiency is the product – not the sum – of two or more ratios; for instance where we consider efficiency of a steam plant as the resultant of those of the coal, the fireman, the boiler and the engine.

The aims of efficiency are various. They may be either creditable or the reverse. Their praiseworthiness has little or nothing to do with the degree of efficiency desired or attained. The aims may be either ethical or material; in either case either creditable or not. In general, the study of efficiency leads to cutting out wastes of time, money, material, and muscular or mental force.

Early difficulties, in efficiency study. Some find this study in the beginning dry and uninteresting, because they fail to see what is beyond the first investigations and definitions. But they will find that the theme unfolds systematically and symmetrically; that with each succeeding lesson the work will be more easy, the results more apparent. the study might indeed be compared to trying to pull open a drawer that offers stout resistance at first, but succumbs to repeated pulls and shakings, and at last-perhaps even before expected opens suddenly and reveals the contents.

Efficiency study should be compulsory. The fact that there is a fool born every minute should lead to enactments to protect fools, by making them in some degree efficient. A fool is no more responsible for being foolish than a negro is for being black, or than I am for not being handsome, eloquent, or musical. Very often the fool knows that he is a fool – it having been borne in upon him by countless humiliating experiences. Is it not as much Society's duty to protect him from crooks, and against his own weaknesses, as to inspect and treat the teeth of school children, and to insist that feebleminded and cripples shall be aided?

How to attain efficiency. There is no one definite method of attaining anyone kind of efficiency; much less, anyone definite means of achieving all the kinds thereof. There are, however, some means which aid in attaining all kinds:- study, counsel, imitation and practice; each embracing many subdivisions and capable of many applications-even of several definitions, according to the application intended. Results of attaining efficiency. These are many, various, and usually desirable. As a rule they are beneficial both to the one attaining them and to the community. For inefficiency, means loss; usually, to the community or to some member thereof, other than to the inefficient person, corporation; or other causing it. And just as injury to one is apt to be harmful to all, so loss to one is apt to be loss to all.

Therefore everyone, no matter how efficient, should aid in raising the standard of those within his sphere of influence.

The measure of efficiency. Although efficiency has neither weight nor dimensions, it may be measured just as well as can those other weightless elements, electricity, and light – by its effects. Like the navigator's knot, it is a rate: – the proportion or relation between cause and effect, effort and result. A man, a thing, or a manufacturing plant, is 100 per cent efficient when no more result could possibly be got by the same effort; or conversely when a given effort could absolutely produce no greater result.

How to record efficiency. Measurement having been effected, or estimates made, where possible, the results should be recorded for present and future guidance and comparison. The records should be accurate, full, thorough, comprehensible, and comparable with others, whether present, past or future. Graphical records aid in rapid comprehension and comparison.

Comparison of efficiencies. The efficiencies of two persons or things can be compared only when they have been measured under the same or comparable conditions, and the measurements are expressed in the same or comparable units. Thus we could not compare the efficiencies of two cannons when the one was expressed in foot-tons, the other in muzzle velocity.

The zero man. The most pitiful thing that can happen to any man is to have it said of him as in the Bible of Jehoram, King of Judah, "And (he) departed without being desired."

The "zero man" has been described by the author of "Torchy, Private Sec." as "two ciphers on the east side of the decimal point."

The inefficient man has been described by Sewell Ford as "bright from the feet down."

What efficiency calls for.

1. Studying conditions

2. Recording the results of the studies in order to

a. Do away with wastes

b. Develop unused resources.

What wastes are to be eliminated?

1. Those of time

2. Those of space

3. Those of work. (either mental or physical)

4. Those of money or its equivalent

5. Those of worry.

Effort and result. Efficiency is only attained when instead of great effort producing a small result, a slight effort will produce a great result. To express these two conditions as mathematical formulas in the first case

E' > R or R < E

while in the second

E < R or R' > E.

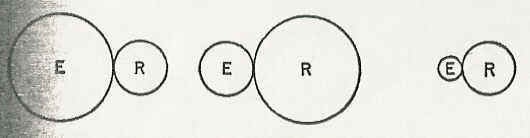

The proportions of effort to result in producing efficiency may be expressed better graphically than algebraically. Here are three pairs of unequal circles. In the first, the one marked "E" is larger than that marked "R." That means, Effort is out of proportion to Result; and we

have inefficiency. In the second pair, where Effort is proportionately small compared with Result, we have some degree of efficiency. The third pair, also, represents Efficiency, but although the circles are much smaller than those in the other pair, it represents a higher degree thereof. Now note that the first pair, although showing inefficiency, may also represent capacity or force. This emphasizes the distinction between efficiency and capacity.

At what age are we most efficient? This cannot be answered in general terms. There are both inefficient and efficient men of every age. Hindenburg and Joffre are proofs that Osler (now lecturing at 80) was wrong in asserting that men cease to be efficient at 40.

QUESTIONS 1 TO 20

The student should read the text over carefully twice, with at least twenty-four hours’ interval, before answering these questions.

1. Give a short definition of efficiency.

2. What is the principle employed by jujitsu wrestlers?

3. How does a crack oarsman illustrate efficiency, as compared with a beginner?

4. Describe the difference between capacity and efficiency.

5. How do strenuousness and efficiency compare?

6. How is efficiency measured?

7. Under what conditions may the efficiency of two persons or two machines be compared?

8. For what does efficiency call?

9. What are essentials in records of performance?

10. What wastes does efficiency eliminate?

11. What are twelve factors in efficiency?

12. How may mental efficiency be increased?

13. Why should old people avoid activities which might risk a heavy fall?

14. What factors enter into physical fitness?

15. What factors tend to increase commercial efficiency?

16. How are military and naval efficiency attained?

17. Give an example of corporate inefficiency (preferably of your own knowledge).

13. What is scientific efficiency?

19. Whose name is most often connected therewith?

20. Give an example of inefficiency of production.

LESSON II

EXAMPLES OF EFFICIENCY

In the previous lesson I explained what Efficiency was, and what it was not; described the different kinds thereof; stated its aims, the method of attaining it, and the results of its attainment. To drive home some of the principles enunciated in these pages, let us examine some excellent examples of efficiency, worthy of imitation or emulation. They are in marked contrast with those given later of inefficiency.

Military and naval efficiency, which are intimately related, consist in achieving the desired result with the least possible expenditure of men, equipment, and cash; usually in the least possible time

"What bearing has this on personal efficiency?" asks the caviler or the unthinking person.

Much. The efficiency of an army or other body of troops depends, when we get down to it, on the teeth and the feet of the individual soldier – on forces, ideals, a directive mind, attention, and almost all of the factors which I give as essential to purely individual personal efficiency.

Orchestral efficiency. In a well-conducted, coordinated orchestra of capable performers, each member is conscious that an error of commission or omission (especially the former) on the part of anyone will result in discord instead of harmony. Each seeks to attain individual perfection in time, tone and expression, and perfect co-ordination with his fellow musicians, with absolute obedience to the leader. This calls for concentration of attention; memory; analysis of individual tones, and isolation of those from different instruments. During a "rest" in his own score, each player must keep the "tact" or time beats in mind, automatically, so as to "come in" again at the rigl1t moment, to the fraction of a second. The leader must both analyze and synthesize effects. His attention must be concentrated on the score, unless supplemented or replaced by memory and habit.

Efficiency in housekeeping. The good housekeeper works according to a time-table and plan, figured out beforehand with reference to the various tasks to be performed, and the time, money and assistance at her disposal.

She saves much work and many a step, by attending to things promptly. When she leaves her bedroom in the morning she turns the bedclothes back to air them, while she prepares and takes her breakfast, instead of leaving the room untouched and wasting all the time during the morning meal. Before leaving the bathroom, she wipes around the washstand, so that work will not want much more afterwards. So elsewhere: if she "goes through the performances" daily she will always have a neat-Iooking home, not need to work to death on "house-cleaning day," and riot have to' excuse herself because her house "is in an awful state." All this work would not take more than a few hours; and she would be ready early to go out and order. (Most women "don't feel like working" after they have been out before the housework is done.) She should choose the food herself, not order by 'phone; for only an important customer can rely on really good wares ordered that way. Many a woman starts meals with table laying. She should first put on the fire all that has to be cooked or warmed; during this process she will find ample tune to attend to the table.

The efficient housekeeper is through long before others, with much less to do and more means to do it with, have finished their task. The good housekeeper is through on time; the poor one only in time – an entirely different matter.

Efficiency in transportation. In the Welland Canal, barges which are too long for the locks are cut in 'two crosswise, the open ends closed by bulkheads, and the sections floated through separately, then rejoined for further towage. This is a good example of efficiency due to initiative, backing invention – (only another form of imagination), and is based on memory, which latter rests on association and attention. Still greater efficiency might be attained by building new locks, but only if the number of long barges would justify it.

See how all the personal efficiency factors which I will describe to you in detail dovetail into each other.

Efficiency in pig raising was shown in Louisiana, where two men selected litter mates eight weeks old. At the end of the fattening season one pig weighed 520 lbs., the other only 61. The expenses were respectively $15.54 and $5; and one sold for $58, the other for $8. This means weight in the proportion of 1 to 8; expenses, 3.1I to I; selling price, 7.25 to 1. Thus, scientific raising can eliminate the notorious "razor-back" hog of our Southern States.

Efficiency in digestion. It is not enough to choose food which will be tasty and nourishing at little expense (there is plenty thereof and good variety thereof) but it should be eaten at such times, in such quantities, and in such order, that the stomach will not be overburdened. Brillat-Savarin's work "Physiology of Taste" shows how each course of a meal should enhance the digestibility of the one preceding it.

Efficiency of office appliances. An office appliance is efficient when it

1. can do all the work required thereof more economically and humanely than could be done without it;

2. can be kept fully employed;

3. prevents errors;

4. does better work than hand.

Efficiency in little things. So many more little things than big ones go to make up our daily life, and their sum is so much greater than that of the big ones, that it is just as well that we should make ourselves efficient therein, as that we should strive to be efficient in the great ones. A dozen two per cents are worth more than one twenty per cent, and usually more easily attained.

Gum a newspaper clipping on a page. Why apply gum first on the top edge and then on the bottom? Why not turn the slip upside down and with one stroke apply gum to the bottom of the clipping and to the place where the top will come?

Watch people opening and folding newspapers in the subway cars, w here there is a strong draft. Most of them endeavor in vain to bring the paper around against the wind. "Once in a blue moon" you will see some one who takes advantage of the draft to turn and fold the sheet for him. Ask some one to sharpen a piece of blackboard "chalk" – (so called because there is not a particle of chalk therein, it being made of plaster of Paris and flour). After he has whittled away about a third of the length of the piece, trying to sharpen it by knife strokes from the butt towards the tip, take it away from him and sharpen it in four strokes, without wasting any material, by cutting from the center of the small end towards the butt.

These are but little things; but they mark the inefficient man as surely as does spitting against the wind, or getting out of a moving car by stepping backwards, brands the unpractical man. When one gets into the habit of asking oneself before putting a postage stamp on an envelope, striking a match, or opening a four-fold rule, what is the best way to perform the little task, the asking habit wi11 grow, and there will be a great increase in efficiency caused by the sum of the time and motion savings both in the countless little things, and in the more important ones.

Efficiency is a matter of development. "By patience and perseverance the mulberry leaf becomes satin." In like manner, no efficiency can be attained by sudden methods or series of lessons. All that lessons and lectures can do is to point out how to find out what not to do, and the best way to discover by experience and counsel w hat is best to do. Fortunately, the rate of growth in efficiency gradually increases – so that progress, while slow and perhaps discouraging at first, becomes with time more rapid, satisfactory and profitable.

Increase of efficiency with practice. As a broad general principle, no one can expect a worker to do a certain task the first time as last or as well as later. This is the result partly of study, partly of imitation, and in part of automaticity or habit. Confidence and contentment, also, exert their influence, as does the hope of fair and immediate reward.

Sources of efficiency. To parody a well-known quotation, "some men are born efficient, some attain efficiency, others have efficiency thrust upon them." The latter seem to be in greatest number; but the second class, composed of those who attain efficiency by their own efforts, whether or not aided by the suggestions of others, and whether or not inspired by the hope of fame or reward, is the one from which most is confidently to be expected.

It is not alone what a man eats, but what he digests; not what he digests, but what he properly allocates among his various members and organs, that makes him strong; not alone what he allocates, but how he uses the structures built up in the system, that makes him efficient.

Examples of inefficiency. An excellent and we1l known way to teach anything is by giving an "awful example." Temperance advocates understand and apply this. By pointing out faults, lacks, weaknesses, and discrepancies, mell and things may be improved. I give here a number of more or less glaring examples of inefficiency in various lines, hoping that they may "point a moral itnd adorn a tale."

Are we Americans inefficient? A popular slogan of the British people in general, and of the British soldier in particular, in this war, is "Are we downhearted? "The answer is a thundering-and truthful – "No!" Now if some one should start ilie query ill America "Are we inefficient?" the answer would probably be as resounding and as general a "No" – but it would not be truthful) by several long shots. We are inefficient actively and passively; inside and out; in agriculture, finance, manufacture, navigation, inland transportation, sanitation, education, government and war. Our young men have recently achieved a certain degree of efficiency in the line of "spitballs" and the like. But we have not yet reached the efficiency of the Japanese in a method of reducing to black and white marks the sounds of our language, nor of the French in evolving an easily remembered and applied system of weights and measures. The North German peasant, with a poor soil and nasty climate, raises forty bushels of wheat to the acre right along, while we think twenty from fertile farm land good. Almost every chimney in this country is vomiting good combustible. Our children die at an alarming rate of purely avoidable disease, or are killed by automobiles run by drivers whom inefficient legislation and administration fail to control. Our daily newspapers cannot even make the spelling of proper names (let alone the text) in their headlines, agree with what stands below. Our banks can no more control speculation than our local government can stamp out prostitution. And so on all along the line:-

Then: "Are we efficient?"

NO!

Are we Americans economical? Or do we manufacture at a loss? Take the average farmer. He starts with a young pig weighing 100 lbs. and feeds him until he weighs 250 to 300. The pig constitutes a factory for transmuting corn, mash, or slops, into pork. When he has reached a weight beyond which he cannot go, does the farmer sell him? Not a bit of it. Instead of saying as in, Schiller's "Fiesco"

"Der Mohr hat seine Pflicht getan,

Der Mohr kann gehen,"

he keeps on loading the pig with raw material from which nothing comes but rather poor manure.

In France they do things better. My friend Decauville, for instance, used to buy all the lean kine he could, weigh each, put a zinc tag marked with the weight, on a horn of each, and feed each animal each day one-tenth its weight of spent sugar-beet slices. Twice a week, each beast was weighed; when two weighings showed no further increase in weight, it was sold, because it would not pay to feed into it one more pound of fodder.

Physical inefficiency. Those with general interest in the welfare of the human race teach us that we are inefficient even in breathing; that parts of our lungs are seldom or never visited by the life-giving oxygen of the air, So we are advised to breathe deeply and slowly, to make our lungs efficient; which again leads to increased capacity and efficiency of brain, nerves and muscles. We are physically inefficient from top to toe. The New York policemen were shown to be flat-footed and weak-footed; so were the girls of Oregon University. (Yet in Washington there seems to be no "putting down the foot flat," when cause comes.) Our young men are flat-chested (military training would better that) and some of the old ones too flat-headed.

No middle-aged man should have the right to take his wife or his daughter in his lap, unless he can pick her up and carry her, in case she faints or sprains her ankle. .

In 1915 the U. S. Marine Recruiting Bureau in New York City received 11,012 applications for enlistment, but only 316 were able to pass the physical examinations. That ciphers up to only one in 35; or 2.87 per cent. Not three out of a hundred, physically efficient! The examiners were probably inefficient as well, refusing many who would have been good marines.

Agricultural inefficiency. America averages only sixteen bushels of wheat per acre. Forty should be raised without difficulty. Germany is now doing it, on poor soil and in an unfavorable climate.

Either we plant unprofitable varieties, or we sow such kinds and at such times that the product comes all at once, and cannot be marketed to advantage.

Mining inefficiency. Our coal-mine owners are about as uneconomical of our "black diamonds" as our lumbermen of our forest wealth-as witness the immense "culm" piles in the mining districts. And the miners say-I know not with how much truth-that too many mines have been opened out; that if all were worked, four hours a day would supply the entire demand of this country.

Lumbermen's inefficiency. Our forests are disappearing because we do not replace the trees which are felled, and do not even take care to cut them close to the ground – so that from ten to twenty per cent of the lumber is wasted. Also, we fell full-grown trees so carelessly that they destroy young ones in falling.

Manufacturing inefficiency. Our manufacturing is done inefficiently because we do not use our waste or by-products – some of which are worth more, if properly utilized, than the so-called main products.

We wait for a foreign war which upsets our entire textile industry, and hampers almost every other, before we turn about and make benzine and toluol from waste products that have been escaping for the last fifty years. We delay until the supposed sole supply of potash has been cut off, before we look around us. Then we find that we have potash in abundance:- it only requires to be extracted.

We have been importing nearly $120,000,000 worth of chemicals per year. Dr. Thos. H. Norton says that we could make most of them 9urselves without any difficulty. But we are satisfied to "let George" – or rather Wilhelm – "do it."

Military and naval inefficiency. Not satisfied to elect a baseball player as member of our legislative body, we put him on the Committee which has to determine of what our army shall be composed. There is not one branch of either army or navy in which we are efficient.

Inefficient representation abroad. Our diplomatic service is usually bad enough; our representatives being chosen with no regard to ability or experience. But our consular service is a laughing stock among the nations. A life insurance company which would appoint its representatives abroad on such a plan (or lack of plan) would soon be in the receivers' hands.

Judicial inefficiency is so common that about one-half the decisions of the lower courts, when appealed, are reversed by the courts above. Think of the time and money lost to the American people by this fact alone.

Legislative inefficiency. About the only thing in which our legislators have proved themselves efficient is in their excellent understanding of the subject of pork.

Inefficient enforcement of the laws. It is said that...

(Unfortunately, a page is missing at this point)

...to be had merely for the asking – yet they continue to show an "efficiency of use" of 40 per cent, or even less.

"We do not eat veal because it is cheaper than other meats, but simply because we like it and are willing to pay for it. Besides this, about two-thirds of the calves that come to market for slaughter are from the dairy breeds, such as the Jersey and Guernsey:- little-weight animals that no sane feeder would put a pound of feed into, because he couldn't hope to get weight enough back from it to pay for the feeding. That class of animals are JniJking-machines pure and simple. The dairy men, after keeping enough of the calves to replace their old cows, are forced to get rid of the rest, and the most profitable plan is to dump them on the market for veals." Technical World Magazine.

Inefficiency in letter writing. If we want to borrow a knife, we don't say to the owner "My dear Mr. X, will you please lend me your knife? I remain, dear Sir, Very truly yours, Y. Z." We say at most: "Mr. X, will you please lend me your knife ?"

Then why put the "Dear Sir" and the closing phrase, on a letter? And why say: "I have received your letter of Nov. I2th and in reply would state that so-and so?" "Replying to your letter of Nov. 12th" covers the ground. It could not be replied to, unless it had been received.

The same principle applies all through ordinary letters, particularly on business.

Typewriters' inefficiency. Are our typists efficient? To judge by the one in a certain "efficiency" office, who wrote me "Appreepo" of something or other, I would answer "No." (The letter was signed by the head of the department in question.)

National wastes. The United States outlay for medicines amounts to $500,000,000 per year; 80 per cent of this ($400,000,000) being without physicians' prescriptions. This last amount is more than the cost of the Panama Canal.

"Inefficient population." Some one put the question to a management missionary "What would you do where you found the entire population inefficient? You could not fire your labor. They would get their pay and then take two or three days off." The answer was evasive. It practically amounted to the fact that "it was a job for the mover." For all that, few cases are hopeless. There is in al1 Sodom at least one righteous man in every community there must be some one who has not mental beri-beri or hookworm disease, and can be used as an experimental guinea-pig for the rest. In fact, I cannot conceive of any factory not having had to close its doors long before the whole population had become inefficient; because perhaps the management itself was partly responsible.

Inefficiency in trifles. Some persons put on the left glove first, strike matches lengthwise of the box, and in a hundred other ways show that they pay no attention to the little things of this life-therefore are most likely to be inefficient in important matters.

But the left hand is less capable than the right, and any gloved hand less so than the same one, ungloved. And the right hand being usually a trifle larger than the left, while both gloves are the same size, the right glove fits the more tightly of the two. Now, why handicap the naturally least capable hand still further, artificially, and then assign it the more difficult task?

"In the matter of the matchbox – every time that a match is struck, part of the prepared striking surface on the box is destroyed – so why ruin a long streak , thereof, when a short one will serve?

No doubt you do, or at any rate have done many such petty things the wrong way. Now I want you to analyze the first ten things you do in the morning. You will probably find that in at least eight you are making too many motions, taking unnecessary time, or doing them the least efficient way. If this is the case with petty things that you have done thousands of times without noticing that you have done them inefficiently, is it not likely that important ones-all of which may be analyzed into a great number of simple ones-have not also been so done? The analysis is worth making -commencing on the least complicated, and leading up to the more complex and important.

Losses by inefficiency. Some of the "losses" by inefficiency are losses to one individual yet more or less corresponding gain to some other person or persons. Thus if in wagoning coal, five per cent is spilled on the road and gathered up by some poor person, there is no absolute loss. If in reaping a field five per cent of the grain is not garnered, but four-fifths of this is gleaned by several persons, we have a loss of five per cent to the owner, a gain of four per cent to the gleaners, and absolute loss of what is not gleaned.

The principal losses, however, from inefficiency , are absolute. No one benefits by them any more than by the black smoke arising from imperfectly (i.e., inefficiently) burned fuel. In the United States alone these losses amount to billions of dollars a year. Brandeis says that American railways lose a billion dollars annually by inefficiency. While there are no data for such a precise statement, it is probably not overdrawn.

How to detect inefficiency. Often, inefficiency reveals itself to the observer; less often to the inefficient corporation-municipal, governmental or other. But as we detect very slight deviation from the vertical by the use of a plumb line, from absolute' planeness by a straight edge, so, inefficiency may be detected by the application of standards of measurement, with due reference to the recognized or desired standards of attainment. And just as we would not expect a street pavement to be nearly absolutely flat as a planer table or a printing press bed, we must not expect or even hope to see as high a percentage of efficiency in an ordinary bookkeeper as in a C.P.A. (Certified Public Accountant.)

QUESTIONS 21 TO 40

21. Give an example of inefficiency of production?

22. Of supply.

23. Of use.

24. Of quality.

25. Of assignment.

26. Of housekeeping.

27. In transportation.

28. Of office appliances.

29. In American military matters.

30. In American naval matters.

31. In little things, from your own personal knowledge.

32. Are Americans efficient?

33. Give an example of American extravagance.

34. Why have so many women weak ankles?

35, In what do American farmers show inefficiency?

36. In what are our mining industries inefficient?

37. Our lumbermen?

38.. Our manufacturers?

39. What proves our judges to be incompetent?

40. Our schools?

| Second Work Sample: Fifty Years Hence, or What May Be in 1943 |

"Fifty Years Hence" is a quasi-fictional work with the evident intent by Robert of making a sincere or "serious" effort to predict the future, again from an almost purely Modern point of view. The fictional character who "tells the story" is 21-year-old Francis Ainsworth (engaged, coincidentally, to Estelle Morton, whose surname is the same as the mother of Robert’s deceased wife.) Robert himself would have been 42 at the time of the book’s publication. The story takes place in New York City.

Through his affiliation with the Masonic Lodge, Francis hears a fascinating lecture, based in Masonic mysticism, by one Roger Brathwaite. Francis befriends Roger, who shares some of his future-prediction methods, and a manuscript predicting conditions in 50 years. However, before the friendship can flower, Roger is mysteriously killed in a fire at his home, which also destroys his lifetime’s worth of records and predictive methods. All that Francis has left is the borrowed manuscript, which is reproduced below, along with some of the introductory paragraphs.

As a side note, Robert dedicated the book to his children, "Who may perchance, fifty years hence, compare these prophecies with what has then come about." Robert apparently lived long enough (to at least 1940) to make the comparison for himself!

Figure 5 below includes images from a copy of "Fifty Years Hence," including the cover, title page, and dedication (to Robert's children.) This copy of the book also has an penciled inscription, apparently made by Robert -- "To Mr. Lindsay Swift:- with the compliments of the perpetrator. 9/22/93."

Figure 5. Images from the cover and title page of "Fifty Years Hence." Also shown are the dedication to his children and a penciled inscription by Robert to Lindsay Swift.

(Note: Text from "Fifty Years Hence" is in preparation for this webpage.)

| References (Besides Robert’s Publications Listed Above) |

1Marquis, Albert N., 1939, Who's Who in New Jersey, a Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men and Women of the States of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and West Virginia, v. 1 - 1939: Chicago, The A.N. Marquis Company, p. 345.

| World War II Report of Captain William Stelling, Robert’s Grandson |

One of Robert Grimshaw’s grandchildren, William Stelling, was an officer in the U.S. Army in World War II. In February 1945 he filed a report of the activities of his unit, the Interrogation Prisoner of War Team #30, for approximately the preceding year. The report included the D-Day landing in June 1944 and the ensuing months of fighting in France.

The text of this articulately written report is presented below (paragraphs introduced by webpage author to improve readability.) It is apparent from the text that Captain Stelling’s assignment to a Prisoner of War team was due at least in part to his ability to speak German. Thanks again go to Mike Stelling for providing this interesting report.

104th (TIMBERWOLF) INFANTRY DIVISION.

ARMY POST OFFICE 104, US. ARMY

PRISONER OF WAR ENCLOSURE.

February 4th 1945.

Subject: Interrogation Prisoner of War Team #30 Activities since Spring 1944

To: Lt. Col. George Danker, Executive Officer, Headquarters Military Intelligence Service, European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army, Post Office, 887.

In January 1944, Interrogation Prisoner of War Team #30 was sent from Prisoner of War cage #1 near Broadway, Worcestershire, England to Tavistock in Devonshire to join the 29th Infantry Division which had been in England for a couple of years by that time. The G-2 thought it would be a good idea for our team to stay with the various types of units within the division for at least a week at each place. Thus we became Artillerymen, Ordnance, Engineers, and so on down the line, and in this way we became acquainted with the entire division and its structure and the various other elements, in turn, got acquainted with us, coupled with indoctrination in Prisoner of War and Intelligence functions. All members of team #30 lectured on Prisoner of war and allied subjects, serving a dual purpose, e.g.: the lecturer was obliged to make deeper study of his subject materials, thereby enhancing what he had learned at Camp Ritchie (I discount the practical experience of strategic interrogation at Prisoner of War Cage #1 for practical purpose at this time), gained a new sense of confidence in himself and his responsibility to other personnel in the division; the division personnel became well acquainted with the lecturer and adopted him thenceforth as a rightful member of the division family.

While I presently reflect on whether or not it has done Interrogation Prisoner of War Team members good to have participated in all exercises, such as, "cannoneer's hop" with the artillery and bridge construction with the engineers during these "lehr monate", later experience on the field of battle has proven these occasions as no waste of time or energy. The Interrogation Prisoner of War team, though attached to an Infantry regiment or division headquarters, can more effectively apply their all-around knowledge born of practical experience with other units such as, Artillery and Engineers, when plying Prisoners of War with questions based on essential elements of information of interest to all types of units within a division command; hence, the original members of this team are grateful for the experience of having served as Ordnance men for a period, as Artillerymen for another period, etc. Thereby a solid foundation was built and an appreciation for all units' work within a division was engendered.

There were two other Interrogation Prisoner of War teams within the division doing similar work with their particular regimental combat teams. In March of 1944 it was decided to switch teams when the G-2 was changed, hence, Interrogation Prisoner of War Team #30 was attached to the 115th Infantry Regiment in Bodmin, Cornwall. Here, until we were sent with the regiment to a martialing area prior to D-day, we participated in all types of maneuvers and difficult field training in preparation for the "big show". One of the men, a Staff Sergeant, developed a chronic skin infection and another man, the T/3, was too old for the active work we were called upon to do, so they were replaced by two men who reported to me while we were in the martialing area a few days before we embarked. The replacements found it a rather sudden transition to be thrust in a "spearhead outfit" after the relatively relaxed tempo of existence under Field Intelligence Division auspices in Broadway, but adjusted themselves to the threatening conditions as real men will, or won't, as the case may be. I found it desirable to increase discipline, not only for our team's sake but for the other elements with which we had to work. It was at this time I stressed neatness of dress to my men. I had noticed a tendency toward slovenly dress among soldiers, especially among my men to wear their uniforms as though they were civilian clothes. I "harped" on this daily for a while until I was satisfied that the condition was corrected. I felt it was especially important for men who were going to deal with German military prisoners to be meticulous in their dress, clean-shaven, and military in manner. They were to carry out this idea all the more thoughtfully if conditions in the field would make it difficult. Later incidents proved the value of this measure.

"The horrors of anticipation are worse than the realization" could well be applied to the feelings of the team individuals during these last dark, tense hours in the martialing area where everyone worked most assiduously not to betray their true feelings. One of the replacements reminded me of the time when I came in to his tent to get acquainted. He said I looked very Prussian and cold, there was no color in my cheeks and my attitude was stiff and formal. This suggested to him the seriousness of the invasion phase more than anything else, apparently. I was not aware of any change in my attitude, however, it is quite possible that the tenseness of the time had affected me this way as it had others one way or another.

The morning we drove the last miles to the ramps where the Landingship Tanks, Landing Craft Infantry and other invasion craft were waiting with open maws to receive us, spirits rose perceptively. This was IT! We were crowded on a Landing Ship Tank, a swarming mass of machines, vehicles, and khaki clad humanity. That was, to the best of my recollection, on or about the 29th of May. We were escorted to the English Channel by a congress of sea-going craft that exceeded my most extravagant expectations - destroyers, rocket ships, cruisers, mine sweepers, PT boats and others not mentioned in the daily briefings. This impressive assemblage of ships and craft was in itself enough to divert the thoughts of the soldier cargo on this overcrowded Landing Ship Tank from any dispiriting fears they may have had. We had no need of a chaplain at this stage of the game. The zig zag course along the channel was more like a Naval game of follow the leader; the chalk cliffs appeared and disappeared intermittently and many of us were sorry to leave England. On June 4th we had a day of talks by various officer personnel, last minute instructions and warnings, bits of sage advice on what to do and what not to do. I led the ship's personnel in singing of the national anthem and was shocked to learn how few people really knew the words. Or possibly most people were thinking about German planes and E-boats at that time, for we were in THAT zone. Actually, it was a most calm and peaceful-seeming cruise, an illusion somewhat contradicted by the show of lethal weapons and war material.

On June 5th tension and excitement grew again. Flights of our planes were skimming the waves, dipping their wings at us and flying on to the direction we knew now must be ours too. All sorts of inspections were held on this day and vehicles were given the last phase of water-proofing. Shortly before midnight we heard the C-47s droning above us carrying the Airborne units to the H-minus 6 mission. We saw the flashes of bombings on the Carentan Peninsula, but heard no rumbling follow-up as yet. Dawn of D-day was ominously quiet. The sea was gray and quiet, and the expected horizon gave no indication of what was to occur shortly after. H-hour took possession of us with all known faculties and senses alerted and tingling, and some that were not known to us now evinced themselves. We were a few hundred yards off the beach. The curtain had parted before the deceiving overture had finished. This was REALLY IT!

The village of Colleville-Sur-Mer was plainly visible to us. The water breaking roughly on Omaha Red beach (aptly called "Red" beach) was just a few yards from us now and the symphony of cannon, small arms and bombs now reached our offended ears. Mines exploded, taking with them in their giant upward surge and splash an Landing Craft Infantry or other smaller craft. Hell could show no greater fury than this, an awe-filling panorama of invasion night, noise and destruction, too big for the eyes to encompass, the point beyond "which" in one's wildest imaginings. We were very much in it. The missiles from shore installations were reaching our ship, their whistling and whining, then, new, soon to be daily song. M/Sgt. Birnhak and I were due to go on shore at H-plus 3 but were delayed a couple of hours by the congestion in front of us and some mysterious conditions known only to the Navy personnel. Wounded were already coming in on Ducks.

Some German soldiers, wounded, were being brought to our ship and each of us was very eager to be the first to interrogate them. There were two of them to begin with. One was a Russian from the "Ost" battalion and the other was from the 352nd Infantry Division, to the best of my recollection. It was difficult to get near them firstly, because of the curiosity gazers milling about them and, secondly, they smelled so, one might say, volatilely. The Prisoners of War were talkative enough but the information we had from them was of little use to our S-2 when we finally reached him two days later. We learned about shore defenses from them (radioed immediately to nearby battleships for sixteen inch gun missions); we learned their organization, what weapons they had; and some probables as to what reinforcements might be expected if the invasion were to have struck at this beach. It was a complete surprise to the Germans that the invasion took place at this time and sector, according to the Prisoners of War. I began to appreciate by what they unfolded, the enormity of Intelligence planning, completeness and accuracy of information from all the various intelligence agencies. The information I had been given in briefings was somewhat confirmed by Prisoners of War (later on much more so) and brought more sharply to mind the responsibility I and my crew now had in serving the S-2; how faithfully and accurately we must record what Prisoners of War had to say.

Sergeant Birnhak and I took leave of Lieutenant Puffert, Corporal Beer and others on the Landing Ship Tank and soon found ourselves in the midst of the bloody mess on the beach. The two we had left behind on the Landing Ship Tank were to come in the next day with the jeep and proceed to the Command Post planned for that day's objective. T/3 Koppel and T/5 Mayer were to come in on our about D-plus 8 with the other jeep and trailer. So it wasn't until D-plus 8 that the whole team was assembled at Cartigny l' Epinay. I remember the place well because I met a lovely girl there, the only really attractive girl I met in all of Normandy. But that is another story. The team at that time was composed of the following personnel with the ratings of that period: 1st Lt. William T. Stelling 1st Lt. Harold R. Puffert M/Sgt. Jack O. Birnhak T/3 Richard U. Koppel Cpl. Peter Beer T/5 Louis Mayer. Sgt. Birnhak and I were to make contact with the S-2 in all possible haste and prepare the way, so to speak, or the other team members.

I shall omit the gory details of dead and wounded we staggered over and by, both American and German, though mostly American at that time. We clambered up a sandy trail, intermittently falling on our faces and digging in the sand with our fingers to avoid being hit by mortar, spraying machine gun fire and an abundance of 88's. All we carried was a couple of fragmentation hand grenades each, some K-rations, a Tommy gun and a 45. automatic pistol; plus our water-soaked lower bodies and the sand, which was already chafing and rubbing all our moving parts. There was no sign of the 115th Regiment.

We made our way to a group of trucks, engineer personnel mostly, and talked to some PWs that were there. Nobody seemed to know what to do with them, so we directed them to the beach where a collecting point was being formed by some rather confused and breathless MPs. Shells were falling all over the place and it was difficult to keep people from shooting the PWs. Again, we went up the sandy path to the gathering of trucks, some of which were hit and on fire since we'd been there last, but this time we ventured to go in the direction of St. Laurent-Sur-Mer where heavy fighting was going on. The artillery was thick and heavy enough to justify a few hours stay in some freshly dug holes near a hedgerow.

When the fire had subsided a bit and our second wind had returned we reached the edge of town and found ourselves with some lads from 175th Infantry Regiment 29th Division dug in, waiting for a scrap with some enemy elements that had not been cleaned out of town. I asked a few officers where the 115th was. They were supposed to be in this spot and, obviously, were not. "Oh, they're down the road a piece", "that a-away", "you'd better dig in for the night" and other mixed Texan and Maryland mouthings were well meant but unhelpful. We had orders to join the S-2 in all possible haste and it was my intention to do just that. The only organized group we met at that time were the people from the 175th; the others were small bands of lost souls (like ourselves) and stragglers out to win the war for ourselves, or so it seemed. It was virtually every man for himself in the initial stages; kill or be killed.

We attempted to crawl, creep and snake our way down "that a-away where the 115th was supposed to be and were making precious little headway. It soon became dark, though the sky was morbid red from the burning buildings before us. It was useless to attempt going further under these conditions, though later we wished we had for where we were was a particular hot spot. We had occasion to fire our weapons for the first time from the holes where we stayed. What a relief to know they worked properly. Someone was zeroing in (on) us from our left, so Sgt. Birnhak sprayed the area with the Tommy gun. A ghastly, sleepless night thundered and wore into the day. Long single files of doughfeet, crouching as they sneak-marched along the road, were going past us so we left our holes and soon overtook the head of the column of 2nd Infantry Division men coming in from their landing.

We went a mile before we encountered anyone alive along that road and then met some Rangers coming our way with PWs. We asked them if they had seen any 29th people and they pointed down the road punctuating the gesture with a spurt of tobacco juice from their mouths. At the next small village we met some 175th men who told us that the 115th was at Deaux Juneau, a small town a few miles inland from the beach. We couldn't take a direct route to Deaux Juneau so we attempted several by-ways in that direction. In each instance there were chattering German machine guns to prevent our getting through. There was no definite main line of resistance the first two days, strictly speaking. The unit attacks were by columns of battalions or regiments which by-passed as many German units as they could, it seemed to me.