John Grimshaw's Life in the Coldstream Guards

John Grimshaw's Life in the Coldstream Guards

John Grimshaw's Life in the Coldstream Guards

John Grimshaw's Life in the Coldstream Guards

Webpage for John Grimshaw, Coldstream Guards Soldier and Lancashire Weaver

John's life after his enlistment in the Coldstream Guards, is described by Anne Grimshaw and is provided in a companion webpage. Included in this description are the following topics:

What Did John Carry When on Campaign?

| Website Credits |

Thanks go to Anne Grimshaw for providing the following information on John Grimshaw's life in the Coldstream Guards.

As a private in the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards (or 2nd Foot Guards and one of the élite regiments of Foot Guards), John Grimshaw was paid 1s-1d per day—a penny more than a private in the line regiments of foot. Out of this, he had to pay for bread and meat, 'messing' and other 'necessaries'. After all the deductions he was left with about 5s-6d.

No doubt army life took a bit of getting used to. It was very class conscious but John probably found this unsurprising and was scarcely aware of it. It was just the way life was. After all, it was little different from squire and tenant on some of the Pennine estates, or mill owner and factory operative. When it worked, it worked well with everyone 'knowing their place' and the 'high-ups' keeping a benevolent eye on the 'lower orders' unless they had the temerity to step out of 'their place'. There were even officers as young as himself but they came from 'upper class backgrounds' and had bought their commissions. It was all a part of the normal pattern of life. Aspiring to a commission would have been unthinkable for the likes of John Grimshaw. He began as Private John Grimshaw and Private Grimshaw he remained.

Three years after John enlisted in 1806, the army establishment had fifteen 2nd Battalions that served with the Duke of Wellington in the Peninsula (1808-14).

Most British infantry regiments were composed of two battalions. Normally only one battalion was sent on campaign, the other serving as a depot unit at home. At full strength a battalion comprised a headquarters, eight battalion (or centre) companies and two flank companies—Grenadier or right flank and Light (infantry) or left flank. The main role of Light Companies was to deal with enemy skirmishers and sharpshooters. At the battle of Waterloo in June 1815, John was a member of Lt. Col. J. Walpole's Company—the Light Company. (PRO WO12/1712) but it has not be possible to tell exactly when John was transferred to the Light Company from a battalion company.

Average battalion strengths while on campaign were: Line and Light—500 to 600 men (50-60 men per company) and Guard and Highland—1,000 men (100 men per company). The crack Light Companies of the British Guards regiments were some of the best men in Wellington's army. They were composed of agile men and good marksmen, used as skirmishers and were relied upon to use their initiative—so John was amongst the best. Nevertheless, the Duke of Wellington referred to his soldiers as "the scum of the earth".

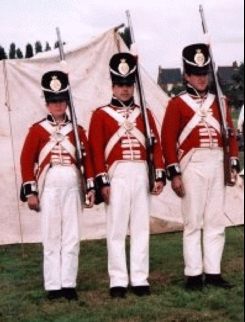

When John Grimshaw enlisted in the Coldstream Guards he would have been issued with the standard red infantry jacket that was cut square across stomach with the skirt tails sloping sharply away. The lace 'metal' across the chest was gold pointed loops in pairs. The regimental facing colours on collar, cuff and shoulder strap were blue. Representations of the uniform of the Coldstream Guards at the time of John's enlistment are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Re-enactor photos showing Coldstream Guard appearance at the time of John Grimshaw's enlistment. Thanks to the Coldstream Guards re-enactment for giving permission to Anne Grimshaw for use of these photos. Their website is at: http://www.civilwardrobe.demon.co.uk/moncks1.htm

By 1812 grey-blue trousers in cool weather and white linen or duck trousers were worn in warm weather. During the hot dry Spanish summers of 1810/12 when John had been in the Peninsula, he must have longed for a change of clothing but replacement of uniform was erratic. He'd probably never sweat so much in his life: the Lancashire Pennines were often shrouded in mist with a seeping dampness that chilled to the bone.

But Spanish nights could be cold too and it was then that greatcoats came into their own—or would have done so had they been sufficiently well made to protect their wearers for the elements. Frequently, though, they were so badly made that they fell apart. After one action in which John took part in the Peninsula, Ciudad Rodrigo in 1812, soldiers simply abandoned their greatcoats as not worth wearing, much less carrying.

Shoes were another problem. New supplies were erratic and it was a case of improvising with local materials to make any kind of foot protection. A cheap and easy method was hide from a newly killed bullock from the field butcher, cut into a foot shape and tied around the foot like a moccasin. Another locally made shoe was a hemp sandal which proved to be ideal on the steep, slippery mountain slopes but would have hardly passed muster back at home.

John would not have been issued with gloves. Such accessories were for softies not tough rank and file however, he would have improvised by pulling down the sleeves of his flannel shirt and tying them over his hands like mittens.

By the time John was a veteran of nine years in 1815 the jackets were smarter and better fitting, probably the result of the army having returned from the Peninsula and enjoying a year or two of peace to take stock and re-outfit before taking on Napoleon again.

When John was in an élite flank company—the Light Company—he wore 'wings' of cloth at shoulders: blue for Foot Guards edged with regimental lace and with darts of regimental lace across the shells.

At all times during his service John would have been expected to be impeccable in his conduct: obedient, unquestioning, loyal and uncomplaining. In addition, his pride in the regiment would never falter. His uniform had to be immaculate as well as his equipment and weapons. This was not always possible on active service when replacement clothing did not arrive and uniform had to be patched and turned. Even at the battle of Waterloo, the Guards were wearing old, patched clothing that had been issued over a year ago and had withstood months of campaigning.

When not on foreign service, the Coldstream Guards, along with the other Foot Guards, and regiments of the Royal Household, and it was easier to maintain appearances. John would have been present on such state occasions as Trooping the Colour as well as being on guard duty at St James' Palace and Windsor. It must have seemed a far cry from his days as a weaver in the edge of the Lancashire moors.

Until 1812 John had worn the 'stovepipe' shako with a plume in front but this was now replaced by a Belgic shako made of felt (for rank and file). Once John was in the Light Company, the gold cords of his shako were mixed with a distinctive green and its plume, now on the left, was also green.

His cap plate was made of brass; all the Foot Guards had special Star plates and their Light Companies wore a bugle horn motif on the left side of the shako. [??]

The cartridge pouch held cartridges in bundles of ten. For the Foot Guards it was made of black leather and fitted with two small straps and buckles for attachment to the crossbelt. Its flap had brass stamped badges: Garter Star for Coldstream Guards.

The pouch belt was 2.5 inches wide and his bayonet belt 2.25 inches. Beside buckles attached to the rear of the pouch, the Foot Guards had two additional brass buckles and brass tips on the pouch itself, giving their belts a distinctive appearance.

If he was armed with a musket, John would have carried a steel 'picker' and small brush on leather laces or fine chains looped on to a breast button of jacket and around shoulder belts. He had to keep the lock and vent of musket clean. It needed constant attention especially on campaign for just twelve shots would foul up the inside and outside of whole lock area, clog the vent hole from the priming pan and coat the outside of gun with deposit of burned powder.

The turnscrew, stowed inside the pouch lid, was also in constant use, to loosen the jaws of the cock and adjust the position of the flint; few flints were serviceable after more than a dozen or so shots.

Light Companies had buglers, not drummers and their brass-rimmed, copper bugles had green cords.

Unlike his French counterpart, John would not have had to forage for food while on campaign, although no doubt the odd chicken or pig was 'liberated'. However, any food taken locally had to be paid for immediately under strict orders from Wellington. This often came as a welcome surprise to the locals who were used to the French army simply helping themselves. The British army had its own catering arrangements but, even so, food had to be prepared and cooked by the soldiers themselves.

While on campaign rations consisted of large loaves of coarse bread made by field bakeries. The bread ration was supplemented by 12oz. of beef when available. Hard tack—approximately 4 inches square—resembled a dog biscuit in texture and was about as appetising—even less so when infested with grubs or weevils. There was also rice, lentils or flour. The latter could be made into stodgy, fatty dumplings when rubbed with lard. Sometimes there were peas, beans and local cheese. (Wellington's infantry (1) by Bryan Fosten.)

On campaign, a soldier's billet was of great importance—not that he had any say in the matter. On arriving at a town or village, the Quartermasters would go ahead to select the best houses for the most senior officers, the next best houses for the less high-ranking officers and so on. John would simply have had to walk along a street until he found a house with a chalk mark on the door indicating how many rank and file could be accommodated there.

On 25 December 1811 a schoolmaster sergeant was augmented to the regiment. Was this where and when John Grimshaw learned to write? (Note in Regimental records Vol. 1 1803-81 Cavalry and Foot Guards in the PRO WO 380/2)

The Guards had a long-cherished and proud tradition to live up to. Discipline was, on the whole, very good with few courts martial and those soldiers who were disciplined had generally committed no heinous crimes.

In or on his knapsack:

2 shirts

Blanket

2 pairs of stockings

Mess tin, centre tin and lid

1 pair of shoes

Extra pair of soles & heels for shoes

Pair of trousers

Razor

Greatcoat

Soap box and strop

3 brushes

Box of blacking

Other equipment:

Ball bag containing 30 loose balls

Small wooden mallet to force balls into rifle

Belt and ammo pouch which held 50 rounds of ammunition

Powder flask

Rifle/musket

Canteen

Sword belt

Haversack

The above list does not include the clothing he wore: the shako, jacket, trousers and shoes.

Sgt. Costello of the 95th Rifles claimed in his memoirs that the equipment they carried weighed about 80lbs, which is probably not too far off the mark. The Baker rifle weighed over 9lbs and if he carried the 80 balls (which were 20 to the pound) this was another 4lbs, not including the powder! The greatcoat weighed about 5lbs, depending on the manufacturer, while the standard 'Italian' canteen weighed 3lbs empty. If they carried three days rations in their haversack, that would be another 6lbs (1lb of bread and 1lb of meat per day)c.

Arms were provided by the Board of Ordnance from stocks in Tower of London and other armouries. John's musket, popularly known as a Brown Bess, was officially the New Land Pattern: a 42 inch barrel and weighing 10lb 4ozs. A trained soldier could fire at the rate of three rounds a minute but even so, accuracy, was not the musket's forté. Hitting a target over 100 yards away would have been more a matter of luck than judgement and its effective range was about 300 yards. Nevertheless, when fired en masse as was the tactic of the period, it could wreak havoc amongst the enemy.

Charges for muskets were prepared in cartridges. A waxed or greased paper tube was rolled up around a powder charge, sufficient for priming and firing, and a .753 calibre lead ball. The cartridge paper was cut to a regulation size and rolled with the aid of a wooden former. The powder end of the tube was tightly folded and bent over, to prevent spillage. The ball was at the other end, 'tied off' with a thread round the outside of the paper. The folded end was torn off with the teeth when the cartridge was used.

Loading involved biting the rear end off a paper cartridge containing about eight drams of black powder and a ball. A small amount of powder was poured into the priming pan, which was then closed. The remainder was emptied down the barrel, followed by the ball, which was rammed down with a ramrod. The empty cartridge paper was used as wadding.

The bayonet was triangular in section, 17 inches long and was carried in a black leather scabbard; it was fitted to the barrel by a 4 inch socket. (see Fletcher: Wellington's Foot Guards)

According to the records kept by Sgt. John Biddle of the light Company at the time of Waterloo, John Grimshaw was issued with "firelock 68, musket 68 and greatcoat 543".

Although officers and NCOs wore swords, the rank and file, including John Grimshaw, did not.

The 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards was divided into eight companies and two flank companies—grenadier or right flank and light infantry or left flank.

It seemed to take some time for John Grimshaw's enlistment on 24 October 1806 to filter through regimental records so that his name did not appear until the muster roll of Lt. Col. The Hon. Henry Brand's Company for 25 December 1806 - 24 June 1807 (PRO WO 12/1704) in the list of recent enlistments. Against his name is written '17 March 1807' which is probably the date he was taken on strength of that company. The muster roll was compiled in Westminster and shows three changes of commanding officer in just over two years: Brand as above then Lt. Col. James Philips June 1807 - June 1808 muster rolls (PRO WO 12/1704 and PRO WO 12/1705) and Lt. Col. Matthew Aylmer June-December 1808 muster roll (PRO WO 12/1705) and December 1808-June 1809 (PRO WO 12/1706).

The muster roll of June-December 1809 (PRO WO 12/1706) shows that John himself changed company to that of Lt. Col. Thomas Braddyll. Another change of company commander resulted in Lt. Col. Herbert Taylor being in charge December 1809 - June 1810 muster roll (PRO WO 12/1707). Against John's name on this muster roll is written 'On Command', i.e. under orders to undertake a given duty at some time in the near future.

Another change of company resulted in John being transferred to Lt. Col. Sir Gilbert Stirling's company June-December 1810 (PRO WO 12/1707). The next muster roll, December 1810 - June 1811 (PRO WO 12/1708), shows John still in Stirling's company but he was now on 'Foreign Service' (Peninsula). This muster roll had been compiled at the Tower [of London].

Sometime that year, John changed company again and once more came under the command of Lt. Col. James Philips. This is evidenced by the fact that the men's names were different, not just the commanding officer's in the muster rolls of June-December 1811 (PRO WO 12/1708) and December 1811 - June 1812 (PRO WO 12/1709) compiled in Westminster. John was still on 'Foreign Service'.

Another change of company commander resulted in Lt. Col. George Collier June-December 1812 (PRO WO 12/1709). But in the muster roll of December 1812 - June 1813 (PRO WO 12/1710) John had a familar face as his commanding officer: Lt. Col. Henry Brand in whose company he had first enlisted. The company was on 'Command'. John was back in England. The rolls compiled in Westminster.

A few months later John's commanding officer was from three years before, Maj. Gen. Herbert Taylor as shown on the June 1813 - June 1814 muster rolls (PRO WO 12/1710 and PRO WO 12/1711) and John was again on 'Foreign Service', this time in the Low Countries. He was wounded in the attack on Bergen-op-Zoom on 10 March 1814.

From June 1814 - December 1815 (PRO WO 12/1711 and PRO WO 12/1712) John was in the élite Light Company, Lt. Col. John Walpole's company and still 'On Foreign Service'. This was the period that covered the battle of Waterloo (18 June 1815 and from then on every man who had been present at that battle had 'Waterloo man' or 'W' written in red ink alongside his name. The rolls were compiled at Westminster.

December 1815 - June 1816 muster roll (PRO WO 12/1713) show John now in Lt. Col. William H. Raikes' company 'On duty' (Westminster). John was to remain in Raikes' company until discharged in December 1818. The June-December 1816 muster roll (PRO WO 12/1713) indicates that John was 'On duty' (Tower) but the muster roll (Windsor) of December 1816 - June 1817 (PRO WO 12/1714) shows him listed for the first time as 'Sick' but by June-December 1817 muster roll (PRO WO 12/1714) he had recovered. However, all was not well and the December 1817 - June 1818 (Westminster) muster roll (PRO WO 12/1715, John was again 'Sick'. He had been wounded at Waterloo so perhaps he was suffering the effects of his wounds.

After the battle of Waterloo (when John was wounded for the second time) to his discharge in 1818 he would probably have been put on light duties in barracks in London, mostly in Westminster although sometimes at the Tower and Windsor. There were no formal arrangements for this kind of situation—it was very ad hoc.

Finally, the muster roll of June-December 1818 muster roll (PRO WO 12/1715) has 'Discharged' written against his name and not in the column normally reserved for 'Dead, Casual[tie]s and Discharge'. This muster roll was not compiled until February 1819, his discharge on 14 December 1818 not having been processed for several weeks.

Like every man who fought at Waterloo John was granted an extra two years' service allowance which gave him a grand total of 14 years 52 days with the Coldstream Guards.

John Grimshaw changed companies (or company commander) ten times throughout his twelve years in the Coldstream Guards. It is tempting to speculate that he was such a good soldier that every commanding officer wanted to have him in his company!

Or was Private Grimshaw so awful that each commanding officer got rid of him at the first opportunity?! However, his transfer to another company could simply have been to fulfil manpower requirements.

Foot Guards' battalions had larger establishments (normally 85-100 men) although the numbers of men in John's companies do not show much difference from the norm with 106 men in Brand's company when John enlisted at a time (1806) when Napoleon was a very real threat and the army needed all the men it could get. The maximum of 120 men was in Walpole's company (Waterloo period). This dropped to 70-plus from 1815-18 when the threat from Napoleon no longer existed.

Muster rolls also show casualties ('Casuals'), Dead, Deserted and Discharged. Even when not on foreign service, the six-monthly muster rolls show deaths rates of anything from none to six. Highest death rates, as might be expected, were when on foreign service in Peninsula (early 1811—end 1812) when 26 deaths were recorded. When on foreign service in the Low Countries, including Bergen op Zoom where John was wounded in 10 March 1814 and Waterloo (18 June 1815) when John was again wounded (December 1813—June 1815), 11 deaths were recorded. However, a further four deaths were listed in June—December 1815—probably as a result of wounds inflicted at Waterloo.

Tangier (1680)

Namur (1695)

Gibraltar (1704/5)

Oudenarde (1708)

Malplaquet (1709)

Dettingen (1743)

Lincelles (1793)

Egypt with the Sphinx

Peninsular Talavera War (1809)

Barrosa (1811)

Fuentes D'Onoro (1811)

Nive (1813)

Waterloo (1815)

ehome.t-online.de/home/a.kopp/engldat2.htm

The Duke of Cambridge, as Colonel of the Coldstream Guards, would have been unlikely to have had any acquaintance with Private John Grimshaw! The Duke, as an officer of the Coldstream Guards, was a member of the Nulli Secundus Club .

Alvanley, William, Lord

Anstruther, Wyndham

Aylmer, Matthew

Barrow, Thomas

Beaufoy, Mark

Bligh, Thomas

Bowles, George

Braddyll, Thomas (C/O – absentee landowner Oswaldtwistle area)

Brand, Henry – JG’s first C/O

Chaplin, Thomas

Collier, George (C/O in Peninsula) from June 1810—June 1811 and from June—December 1812. A member of the Nulli Secundus Club, Collier was killed at Bayonne 1814.

Cowell, John

Dawkins, Henry

Dickinson, Newton

Drummond, John

Ferris, B??

Fortescue, Matthew

Henry Gooch became an Ensign in 1812 as Gentleman Cadet from the Royal Military College. He was with John Grimshaw December 1813—June 1814 and also at Waterloo. Promoted to Lieutenant and Captain 28 October 1819. Left the service as Lieutenant-Colonel 11 June 1841.

Harvey, Edward

Kortright, William

McKinnon, Daniel was in John Grimshaw's company June 1810—June 1811 and in Holland in 1814. He was badly wounded at Hougoumont, Waterloo. Noted for his practical jokes and sense of humour, he was a member of the Nulli Secundus Club, historian and author of Origins and services of the Coldstream Guards published in 1833. Married a daughter of John Dent. Died 22 June 1836.

Mildmay, Paulet St John

Moore, Robert

Morgan, George Guild

Percival, George H.

Philips, James (C/O in Peninsula))

Raikes, William Henley (JG’s last C/O post-Waterloo)

Rous, William Rufus became an Ensign in 1812 as a Gentleman Cadet from the Royal Military College. In John Grimshaw's company December 1812 —June 1813. William accompanied his elder brother, John, also in the Coldstream Guards to the Peninsula in 1812 before obtaining his commission.

Salway/Selway, Henry

Shaw(e), Charles

Steele, Thomas

Stirling, Gilbert (C/O in Peninsula))

Stothert, William

Talbot, John

Taylor, Herbert (C/O)

Vachell, Frederick

Walpole, John (C/O of Light Company at Waterloo)

Walton, William L.

Wedderburn, Alexander

Wynyard, Montague

| References |

1Author

2Author

Webpage posted January 2002. Banner replaced April 2011.